Biography

Fasanella, Ralph (Raffaele Fasanello); b. September 2 (10), 1914 (April 20, 1914), Bronx, New York; Italian American; Father Joseph Fasanella, Mother Ginervra (Guerea, Jean) Spano Fasanella; Elementary education; Single; Driver; CP 1935 and YCL; Received Passport# 366776 on February 12, 1937 which listed his address as 2271 Ellis Avenue, Bronx, New York; Sailed February 20, 1937 aboard the Ile de France; Arrived in Spain on March 3, 1937; Served in the 1st Regiment de Tren, deserted and returned on a British freighter by way of Oran; Returned to the US on July 21 (?), 1938 aboard the Huntress; WWII US Navy; d. December 16, 1997, Yonkers, Westchester County, New York, buried in Mount Hope Cemetery, Hastings-on-Hudson, Westchester County, New York; Wife Eve Lazorek Fasanella.Sources: Sail; Scope of Soviet Activity; Cadre; RGASPI; ALBA 235 Ralph Fasanella Papers; Good Fight A; Harriman; La Spagna Nel Nostro Cuore; (obituary) "Ralph Fasanella, 83, Primitive Painter, Dies," New York Times, December 18, 1997, Find-a-Grave# 72182195. Code A

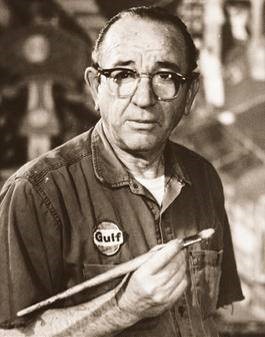

Biography: Ralph Fasanella, born September 7, 1914, was a self-taught painter whose large, detailed works depict urban working life. The child of Italian immigrants, Fasanella was born and raised in the Bronx and later became a member of United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America (UE) Local 1227 while working as a machinist in Brooklyn. Fasanella also fought in the Spanish Civil War with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade and after returning from the war began to work as a union organizer for the UE. Fasanella died on December 18, 1997. - Courtesy Tamiment Library, NYU.

Biography: Born on Labor Day 1914, in Greenwich Village, NYC. Ralph Fasanella was a self-taught painter whose large, detailed works depicted urban working life and critiqued post-World War II America. Ralph Fasanella was born to Joseph and Ginevra (Spagnoletti), Italian immigrants, in the Bronx, New York, on Labor Day in 1914. He was the third of six children. His father delivered ice to local homes. His mother worked in a neighborhood dress shop drilling holes into buttons, and spent her spare time as an anti-fascist activist. Fasanella spent much of his youth delivering ice with his father from a horse-driven wagon. This experience deeply impressed him. He saw his father as representative of all working men, beaten down day after day and struggling for survival. "Fasanella later said that the compositional density of his pictures was influenced by the experience of helping his father deliver ice, which involved removing all the food from customers' refrigerators and arranging it in neatly ordered stacks." Fasanella's mother was a literate, sensitive, progressive woman. She instilled in Fasanella a strong sense of social justice and political awareness. Fasanella began accompanying his mother when she worked on anti-fascist and trade union causes. Fasanella also helped his mother publish and distribute a small Italian-language, anti-fascist newspaper to help support the family. Joseph Fasanella abandoned his family and returned to Italy in the 1920s. This increased the influence Fasanella's mother had over young Ralph, but it also led to some behavioral problems. Fasanella served two stints in reform schools run by the Catholic Church for truancy and running away from home. He later said he was sexually abused ("used as a girl") by the priests. These experiences instilled a deep dislike for authority and reinforced Fasanella's hatred for anything which broke people's spirits. Fasanella later depicted his experience in reform school in a painting titled Lineup at the Protectory 2 (1961). The melancholy image features rows of boys standing at attention, watched over by scowling, ominous-looking priests. Fasanella quit school after the sixth grade. During the Great Depression, Fasanella worked as a textile worker in garment factories and as a truck driver. He became a member of United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America (UE) Local 1227 while working as a machinist in Brooklyn. He became strongly aware of the growing economic and social injustice in the U.S., as well as the plight and powerlessness of the working class. In late 1930s, Ralph Fasanella volunteered to fight in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, an American paramilitary force fighting to support the Second Spanish Republic against the successful fascist rebellion led by General Francisco Franco. After the Spanish Civil War, Fasanella returned to the United States, where he began organizing labor unions. Fasanella joined the UE staff in 1940. He organized a Western Electric manufacturing plant in Manhattan, a Sperry Gyroscope factory, and a number of other electrical equipment and machine plants in and around New York City. One of his later paintings shows a union organizing committee meeting being held in a UE hall. It was during a UE organizing drive in 1940 that Fasanella first began to draw. Fasanella married Matilda Weiss in 1943. The short-lived marriage ended in 1944. In the mid-1940s, Fasanella began to suffer from intense finger pain caused by arthritis. A union co-worker suggested that he take up painting as a way to exercise his fingers and ease the pain. In 1945, Fasanella persuaded the UE to organize painting classes for its members at a local college. He was one of the first members to sign up for classes. Fasanella became consumed by art, and left labor union organizing to paint full-time. To pay the bills, he pumped gasoline at a service station. Fasanella's painting focused on city life, men and women at work, union meetings, strikes, sit-ins and baseball games. He quickly developed a style which spoke to workers and the poor through the use of familiar details. Fasanella improvised a quasi-surrealist style, depicting interiors and exteriors or past and future simultaneously. He painted canvases as big as 10 feet across because he envisioned his paintings hanging in large union meeting halls. Fasanella's art was highly improvisational. He never planned out works, and rarely revised them. He said of his 1948 painting May Day, it "just came out of my belly. I never planned it. I don't know how I did it." His first solo show was at the ACA Galleries in New York City in 1948. One of his first sales was to choreographer Jerome Robbins. In 1950, Fasanella married Eva Lazorek, a school teacher. They had a son, Marc, and a daughter, Gina. Fasanella's opinionated, leftist-oriented artwork caused him to be blacklisted among art dealers and galleries during the McCarthy era. His wife supported him by teaching school. Fasanella's work, however, remained largely unknown for nearly 30 years. While he was acknowledged within labor and leftist circles, his art remained more of a popular curiosity. Fasanella's 5-foot by 10-foot painting, "Lawrence 1912: The Great Strike" (also titled "Bread and Roses - Lawrence, 1912") was purchased by donations from 15 labor unions and the AFL-CIO. It was loaned to the United States Congress, where it hung for years in the Rayburn Office Building in the hearing room of the House Subcommittee on Labor and Education. Following the 1994 elections, a staffer for the new Republican majority in Congress had the painting removed from the hearing room and returned to the owners. The work now hangs at the Labor Museum and Learning Center in Flint, Michigan. In 1995, Fasanella's 1950 painting, Subway Riders, was installed in the New York City subway station at Fifth Avenue and 53rd Street. Fasanella's Family Supper is currently on permanent display in the Great Hall at Ellis Island. By the end of his life, many of the causes Fasanella fought for no longer enjoyed public favor or had been lost. Fasanella himself lamented the decline in the relevance of his work. "It's over. What I wanted to do was to paint great big canvases about the spirit we used to have in the movement and then go around the country showing them in union halls. When I started these paintings I had no idea that when they were all finished there wouldn't be any union halls in which to show them." It quickly became apparent that much of the public fascination for Fasanella's work had relied on the political and socio-economic messages they contained rather than their artistic appeal. As those messages fell from favor, Fasanella was abandoned by many of his strongest supporters. As he told one reporter: "The other day, I called an old lefty pal at 1199 (the drug and hospital workers' union) and offered them my stuff. 'Forget it Ralph,' he said to me. 'We don't want your stuff.' " At his death, however, he had regained a small measure of popularity again. In a press release regarding his death, John Sweeney, president of the AFL-CIO, declared Fasanella to be "a true artist of the people in the tradition of Paul Robeson and Woody Guthrie." - Courtesy of Wikipedia.

Ralph Fasanella Interview, September 23, 1986, ALBA V 48-043, Manny Harriman Video Oral History Collection; ALBA VIDEO 048; box number 4; folder number 23; Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University

Supporting Documents Remebering Ralph Fasanella On Dignity

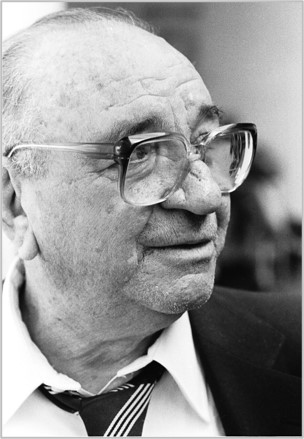

Photograph: Ralph Fasanella, AFLCIO.; Ralph Fasanella, 1984, by Richard Bermack.