In the fall of 1946, the New York photographer Walter Rosenblum–a student and friend of Paul Strand and Lewis Hine–traveled to Toulouse, France, to record the relief work undertaken by the Unitarian Service Committee for the thousands of Spanish refugees living there since the end of the Civil War, seven years earlier. He came back with a series of haunting portraits, 25 of which will be part of an exhibit at the King Juan Carlos Center.

“I had expected to find dejected and tired people,” Rosenblum later wrote, “but instead

discovered bravery and determination.”

Exhibit sponsored by the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives, the King Juan Carlos Center, and the Tamiment Library. With special thanks to the Rosenblum family.

About Walter Rosenblum

Walter Rosenblum (1919-2006)

Walter Rosenblum was born in 1919 into a poor Jewish immigrant family living on New York’s Lower East Side. His mother died when he was sixteen and to comfort himself he borrowed a camera and began to photograph in his neighborhood. He took a photography course at the Boys’ Club where he had a part-time job as part of Roosevelt’s National Youth Administration, and in 1937 he joined the Photo League, an extraordinarily vibrant community of New York photographers. It was there that he met Lewis Hine, Berenice Abbott, Elizabeth McCausland and other notables in the world of photography. He studied with Paul Strand (who became a life-long friend), and worked on his first major project, the Pitt Street series. The League not only provided darkroom space and equipment but also organized lectures and exhibits — Adams, Cartier-Bresson, Doisneau, Lange, Weston, Weegee — and published the legendary Photo Notes, of which Rosenblum was editor for several years. Appointed president in 1941, Rosenblum would be an active member of the League until it folded in 1952 as a result of being included on the Attorney General’s 1947 list of subversive organizations.

Walter Rosenblum was born in 1919 into a poor Jewish immigrant family living on New York’s Lower East Side. His mother died when he was sixteen and to comfort himself he borrowed a camera and began to photograph in his neighborhood. He took a photography course at the Boys’ Club where he had a part-time job as part of Roosevelt’s National Youth Administration, and in 1937 he joined the Photo League, an extraordinarily vibrant community of New York photographers. It was there that he met Lewis Hine, Berenice Abbott, Elizabeth McCausland and other notables in the world of photography. He studied with Paul Strand (who became a life-long friend), and worked on his first major project, the Pitt Street series. The League not only provided darkroom space and equipment but also organized lectures and exhibits — Adams, Cartier-Bresson, Doisneau, Lange, Weston, Weegee — and published the legendary Photo Notes, of which Rosenblum was editor for several years. Appointed president in 1941, Rosenblum would be an active member of the League until it folded in 1952 as a result of being included on the Attorney General’s 1947 list of subversive organizations.

Drafted in 1943 as a U.S. Army Signal Corp combat photographer, Rosenblum landed on a Normandy beach on D-Day morning, after which he joined an anti-tank battalion in its liberation drive through France, Germany and Austria. One of the most decorated photographers of the Second World War, he took the first motion picture footage of the Dachau concentration camp. Rosenblum had an extensive teaching career, beginning in 1947 at Brooklyn College, where he taught until his retirement in 1986. He also taught at the Yale Summer School of Art and The Cooper Union, as well as abroad in Arles, France, in Sao Paolo, Brazil, and in Lestans, Italy. In 1980 he received a Guggenheim Fellowship for his project, “People of the South Bronx.

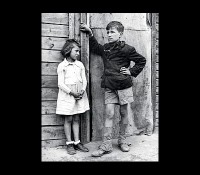

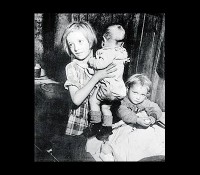

Following in Hine’s footsteps, Rosenblum’s work registers the impact on ordinary people — particularly children — of some of the major events of the twentieth century, from economic depression to colonialism and armed conflict. Working in East Harlem, Haiti, Europe, and the South Bronx, he was drawn to situations that revealed the experiences of immigrants and the poor.

Following in Hine’s footsteps, Rosenblum’s work registers the impact on ordinary people — particularly children — of some of the major events of the twentieth century, from economic depression to colonialism and armed conflict. Working in East Harlem, Haiti, Europe, and the South Bronx, he was drawn to situations that revealed the experiences of immigrants and the poor.

All images are courtesy of Rosenblum Photography Archive, www.rosenblumphoto.org.

The Spanish Refugees

In 1946 Rosenblum returned to Europe as staff photographer for the American Unitarian Service Committee (USC) of the American Unitarian Association to document its refugee relief work in Czechoslovakia and France. The photographs exhibited here were shot in Toulouse in the camps and facilities for refugees of the Spanish Civil War (1936-39), which had ended seven years earlier with the victory of Francisco Franco over the democratically elected government of the Republic. In late 1938 and early 1939, some 500,000 Spanish Republican refugees had crossed the border into France, where they were treated as criminals and herded into concentration camps. In the months and years that followed, more than 20,000 managed to make it to the Americas; several thousands were sent to Mauthausen and other German camps. Many continued their fight against fascism in the French Resistance.

In 1946 Rosenblum returned to Europe as staff photographer for the American Unitarian Service Committee (USC) of the American Unitarian Association to document its refugee relief work in Czechoslovakia and France. The photographs exhibited here were shot in Toulouse in the camps and facilities for refugees of the Spanish Civil War (1936-39), which had ended seven years earlier with the victory of Francisco Franco over the democratically elected government of the Republic. In late 1938 and early 1939, some 500,000 Spanish Republican refugees had crossed the border into France, where they were treated as criminals and herded into concentration camps. In the months and years that followed, more than 20,000 managed to make it to the Americas; several thousands were sent to Mauthausen and other German camps. Many continued their fight against fascism in the French Resistance.

Although Franco had had the active military support of Hitler and Mussolini, he survived the defeat of the Axis in 1945. For the almost 140,000 Spanish refugees who remained in France, often living in appalling conditions, this meant that there was no end in sight to their misery as they could not return to their homeland.

The Rosenblum archives hold 46 photos of Spanish refugees. Some were first published in the December 1946 issue of the Christian Register, the Unitarians’ monthly magazine. They were used throughout the 1940s and ‘50s in fundraising materials for the USC, the Spanish Refugee Appeal, and UNESCO refugee campaigns. One appeared on the cover of the 1946 holiday issue of the New York Times Magazine. Starting in the late 1940s, Rosenblum included them sporadically in exhibits. In 2001, the Reina Sofía museum in Madrid purchased a complete set; in 2005 they were shown in Madrid as part of a Rosenblum retrospective at PhotoEspaña. The 25 photographs displayed here were given as a gift to the Tamiment Library by the Rosenblum family. This is the first time that an almost complete set is being shown in the United States.

Early on in his career, Rosenblum made an important discovery. “I realized,” he later said, “that I worked best when I was photographing something or someone I loved and that through my photographs I could pay them homage.”

About the Unitarian Service Committee

Established in 1940 and led by Charles R. Joy, the Unitarian Service Committee (USC) was one of the most important US-based refugee organizations working in Europe during and following the war, assisting numerous refugee communities throughout the continent. The USC collected funds from many different American refugee organizations — including the Spanish Refugee Appeal of the Joint Antifascist Refugee Committee, led by Dr. Edward Barsky, a prominent New York surgeon and veteran of the Spanish Civil War.