By: Richard Baxell

“It was in Spain that [my generation] learned that one can be right and yet be beaten, that force can vanquish spirit, that there are times when courage is not its own recompense. It is this, doubtless, which explains why so many, the world over, feel the Spanish drama as a personal tragedy.”

– Albert Camus.

Spain in 1931

Spain in 1931 was a country riven by inequalities. Still predominantly an agrarian country, traditional divisions endured between wealthy landowners, doggedly preserving their position, and a huge number of landless labourers and poverty-stricken smallholders, desperate to lift themselves from an existence of near-starvation. One of the largest landowners was the Catholic Church who, in addition to any theological motivations, were thus determined to maintain the status quo. Opposing the Church was the largest Anarchist movement in Europe, with a history of incendiary anti-clericalism. ‘Spaniards’ it was said, ‘followed their priests either with a candle or a club’.

In the very few areas witnessing industrial change- chiefly Catalonia and the Basque regions- corresponding social and political change was largely absent. Aspirations by these regions for some degree of autonomy were bitterly opposed by the Spanish army who, fighting in Morocco to regain an empire which had been lost with the catastrophic defeat to the United States in 1898, strongly resisted any attempts to break up Spain. Large, powerful and extremely top-heavy in officers, the Spanish army had a tradition of involvement in politics; Primo de Rivera’s military dictatorship had ruled Spain as recently as the 1920s. The dictatorship’s legacy was a huge budget deficit at a time when the world was already sinking into economic depression, and its collapse spelled the end for the Spanish monarchy.

In April 1931, municipal elections were taken to be a plebiscite on the monarchy and the result was an overwhelmingly hostile vote against it. The King, Alfonso XIII, realising that he had lost not just the support of the populace but, crucially, the support of the military, fled Spain. Thus, on April 12, 1931, Spain’s Second Republic, la nina bonita, was born.

The Second Republic

For many Spaniards the birth of the Republic was celebrated by exuberant public rejoicing; this seemed to many to signal the beginning of the end for the powerful Spanish elites, and to offer a relief for millions of landless peasants. However, attempts by the Republic to reform powerful institutions like the church and the army, at the same time as challenging entrenched economic interests in the landed, industrial and banking oligarchies, were never able to achieve the successes expected by the Republic’s supporters on the left, while even limited reforms antagonised their opponents on the right. Separation of church and state, modernisation of the army and attempts to reform the deeply unequal distribution of the land were all regarded with horror by the established elites. In addition, attempts to meet the demands for regional autonomy from areas such as the Basque Country and Catalonia, further outraged the Spanish army.

For many Spaniards the birth of the Republic was celebrated by exuberant public rejoicing; this seemed to many to signal the beginning of the end for the powerful Spanish elites, and to offer a relief for millions of landless peasants. However, attempts by the Republic to reform powerful institutions like the church and the army, at the same time as challenging entrenched economic interests in the landed, industrial and banking oligarchies, were never able to achieve the successes expected by the Republic’s supporters on the left, while even limited reforms antagonised their opponents on the right. Separation of church and state, modernisation of the army and attempts to reform the deeply unequal distribution of the land were all regarded with horror by the established elites. In addition, attempts to meet the demands for regional autonomy from areas such as the Basque Country and Catalonia, further outraged the Spanish army.

The situation did not take long to escape from the government’s rather tenuous control. Anarchist and other anti-clerical elements demonstrated their opposition to the Catholic Church by burning churches. The government, unwilling to use the forces of order against workers, some of whom were their own supporters, sat on their hands. If the government’s reformist program had not already alienated the army and church, the government’s inability, or unwillingness, to control its supporters, guaranteed their opposition.

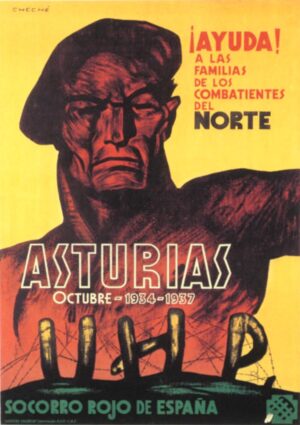

The elections of November 1933 saw a defeat for the republicans and socialists who fought the election as separate parties by a confederation of conservative and catholic parties, including the Radical Party and CEDA. Thus began the bienio negro, the black years, in which the reforms begun by the center-left Manuel Azaña’s government were at best abandoned or, in many cases, overturned. With the entry of CEDA into the government, perceived by opponents on the left as fascistic, the increasingly militant and revolutionary socialist party, the PSOE, responded in October 1934 with a general strike which, in some areas, escalated into armed insurrection. In Asturias, where miners were armed with dynamite, the rebellion endured longest. It was here too, that the governments’ response was most vicious with Moroccan troops under the command of General Francisco Franco committing numerous atrocities. Several thousand were killed or wounded, including women and children, and thousands more were imprisoned.

The 1936 Elections and the Popular Front Government

The elections held in February 1936 saw a coalition of Spanish and Catalan republican and leftist parties, including the PCE, the PSOE, the POUM and the Esquerra Republicana, unite in a ‘Popular Front’, determined not to repeat the mistakes of the 1933 elections. Standing on a platform of reinstatement of the Catalan statute (with other regions such as the Basque regions and Galicia open to discussion), the revival of agrarian reforms and, significantly, amnesty, reinstatement and compensation for all political prisoners, they achieved remarkable success in gaining the electoral support of many Anarchists and won a narrow victory over the opposing coalition of the right.

The new republican government prepared themselves to revive the reformist program of 1931, which had been abandoned by the conservative/reactionary government in1933. However, the unwillingness of revolutionary Anarchists and Socialists to participate in what they saw as an essentially bourgeois reformist government meant that the government lacked vital support from the left. At the same time, as political violence escalated, elements of the Spanish right, who had lost any faith in the Republic, prepared for war. As Paul Preston states:

The elections marked the culmination of the CEDA attempt to use democracy against itself. This meant that henceforth the right would be more concerned with destroying the Republic than with taking it over. (Preston: Concise History, 59-60).

The Military Uprising

The murder of Calvo Sotelo, a prominent Catholic conservative politician, on 13 July 1936 by members of the Republican Assault Guard (itself a response to the murder of one of their comrades, Lieutenant Jose Castillo, the previous day) served as the perfect excuse for the leader of the plot, General Emilio Mola. On the evening of 17 July 1936, the military garrisons rose in Morocco, and the revolt quickly spread to the mainland. The rising began with army garrisons disarming loyal Republican Officers, then declaring the region for the Rebels. The rising was usually supported by Jose Antonio Primo de Rivera’s Falange and the Civil Guard, who often acted on their own if the local town had no military garrison.

In Morocco, Mallorca, Old Castile, Navarre, Aragon and South Andalusia the rising was generally successful. However, in other areas, including the major cities of Madrid and Barcelona, the generals met with bitter and effective resistance from loyal members of the Civil Guard and Assault Guards, and from workers’ militiamen who seized arms despite initial government opposition.

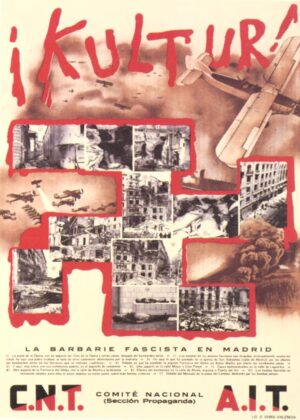

The uprising unleashed a terror in both Republican and Rebel held areas. In the ‘Nationalist’ sector, the military insurgents, aided by elements of the Falange, brutally demonstrated their determination to win by the cold and deliberate application of terror. Opponents of the rising, particularly members of the PSOE and the PCE or the UGT and CNT, but also many thousands of others with Republican sympathies were arrested and executed. In one of the most infamous events of the civil war, Federico Garcia Lorca, the celebrated poet whose offense was to have Republican leanings, was arrested by a local member of the CEDA and murdered. Meanwhile, in the Republican sector, church burnings and the murder of suspected Rightists continued apace as militia units and ‘uncontrollables’ pursued their own revolutionary justice, despite attempts made by the government to contain the terror. The murder of 2,000 rightist prisoners in early November 1936 at Paracuellos del Jarama and the execution of Jose Antonio Primo de Rivera on the 20th were both used by the Nationalists to accuse the Republic of ‘red barbarism’.

The Onset of the Spanish Civil War

At this point the outcome of the rising was by no means certain. The Republicans held most of the navy, air-force and territory, including the capital and the vital industrial regions of the Basque Country and Catalonia. The rebels controlled the majority of the army, though the northern army, under General Mola, was paralyzed by a lack of arms and ammunition, and unexpected resistance from workers’ militias, and the formidable Army of Africa, under the command of General Franco, was trapped in Morocco.

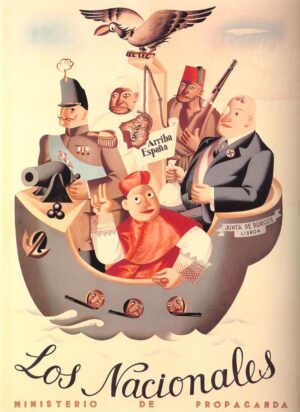

However, forces outside Spain decisively altered the progress of the conflict. Initially, following Jose Giral’s desperate plea for assistance, Léon Blum, the French Prime Minister, had wished to aid the Republic and had authorized the sending of military aid, such as a number of aircraft arranged by Andre Malraux, a French pilot who organized a squadron of French pilots to fight for the Republic. However, following pressure from the British Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, and aware of the dangers of civil war in his own country should his government support the Spanish republic, Blum proposed an international agreement not to intervene in the conflict and a ‘non-intervention’ committee was established in London to oversee the agreement. However, as the agreement was ignored from the outset by Germany and Italy and, later, by Russia, while other neutral countries such as Britain and the United States took no action against firms providing supplies to the Rebels, the agreement was singularly ineffective.

Meanwhile, despite initial reluctance to support what they saw as a risky enterprise (and despite their official adherence to the non-intervention agreement) both Hitler and Mussolini responded to requests from Franco for assistance by sending twelve Italian Savoia-Marchetti S.81 and thirty German JU 52s bombers, which allowed Franco to airlift the Army of Africa across the Gibraltar strait. The Army of Africa then advanced swiftly northwards towards Madrid and by August 10 they had reached Merida where they linked up Franco’s southern zone with the northern zone of General Mola. The rebels then turned on the town of Badajoz, the capital of Extremadura. Despite a desperate defense, the town was captured and a brutal repression followed, during which nearly 2,000 people were shot. Stories and rumors of this savagery preceded the advance of the rebel army on Madrid, and worked considerably to the rebels’ advantage. Militiamen, terrified at the prospect of being outflanked, retreated headlong, often dropping their weapons and ammunition, back along the main roads to Madrid, where they could be picked off with ease by the advancing rebel forces.

Meanwhile, despite initial reluctance to support what they saw as a risky enterprise (and despite their official adherence to the non-intervention agreement) both Hitler and Mussolini responded to requests from Franco for assistance by sending twelve Italian Savoia-Marchetti S.81 and thirty German JU 52s bombers, which allowed Franco to airlift the Army of Africa across the Gibraltar strait. The Army of Africa then advanced swiftly northwards towards Madrid and by August 10 they had reached Merida where they linked up Franco’s southern zone with the northern zone of General Mola. The rebels then turned on the town of Badajoz, the capital of Extremadura. Despite a desperate defense, the town was captured and a brutal repression followed, during which nearly 2,000 people were shot. Stories and rumors of this savagery preceded the advance of the rebel army on Madrid, and worked considerably to the rebels’ advantage. Militiamen, terrified at the prospect of being outflanked, retreated headlong, often dropping their weapons and ammunition, back along the main roads to Madrid, where they could be picked off with ease by the advancing rebel forces.

At the end of September, the rebel army made another detour to lift the siege of the city of Toledo which, crucially, allowed the defending Republicans time to prepare the defenses in Madrid. After another massacre of militiamen, the march towards Madrid resumed. By November 1, the rebels had reached the south-west of Madrid adjacent to the Casa de Campo and University City. Here, at last, the advance was slowed by a defense established by militia units and the desperate population of Madrid. On November 10, 1936, the last ditch defense was joined by an international column of volunteers; the first of the International Brigades, determined to help ensure that Madrid would not fall, that the rebel army would not pass.

The Formation of the International Brigades

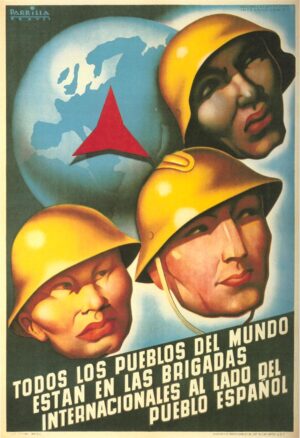

Volunteers for the International Brigades came from over 50 countries across the world to help the beleaguered Spanish republic, many of them with bitter experiences of fighting against fascism and with personal scores to settle. Over 35 000 men and women left their homes to volunteer for the Republican forces, the majority of whom served in the International Brigades and international medical services.

The largest single contingents came from France, Germany, Poland and Italy, though many also came from other European countries, including Britain and Ireland, Scandinavia, Hungary, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia. Other volunteers endured long journeys from as far away as the USA (including a number of African-Americans), Canada, Mexico, Cuba, South America, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. Jewish volunteers comprised a significant minority.

The largest single contingents came from France, Germany, Poland and Italy, though many also came from other European countries, including Britain and Ireland, Scandinavia, Hungary, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia. Other volunteers endured long journeys from as far away as the USA (including a number of African-Americans), Canada, Mexico, Cuba, South America, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. Jewish volunteers comprised a significant minority.

The International Brigades were recruited and organised by the Communist International (the Comintern), which was quick to respond to the influx of foreign volunteers for the Republic. For Stalin, who was concerned at the extent of German and Italian help for the rebels and its potential severely to weaken France, the International Brigades offered an opportunity to support the Spanish Republican Army without intervening directly, and thus reducing the risk of further alienating Britain and France who had established an international non-intervention agreement to limit foreign involvement in the war.

The recruitment of the International Brigades was coordinated by the Communist Party in Paris. The usual route for volunteers was to be smuggled in groups over the Pyrenees. From the border they would be taken the International Brigade headquarters at Albacete, where volunteers would be processed and divided up by nationality, into the different battalions comprising the Spanish Republican Army’s International Brigades.

The War from the Defense of Madrid to March 1939

In response to the desperate situation facing the Republic a true Popular Front government was formed in September 1936 containing, in addition to Republican parties, members of the PCE and PSOE. One month later, despite their ideological opposition, four representatives of the anarcho-syndicalist CNT also joined the cabinet.

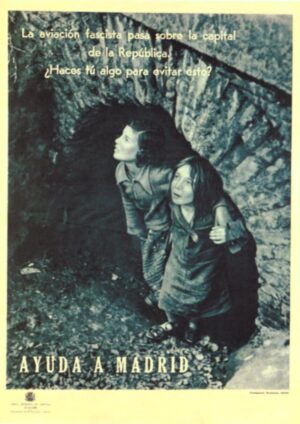

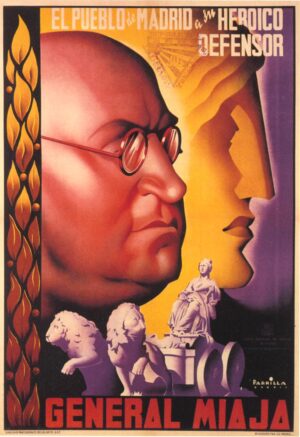

By mid-October, the artillery fire of the approaching Army of Africa could be heard in Madrid and by early November elements of the Nationalist Army had reached the south-western suburbs. The Republican government was so convinced that Madrid would fall that, on 6 November, it left for Valencia, and placed the protection of the city in the hands of a military Junta de Defensa, under General Miaja.

By mid-October, the artillery fire of the approaching Army of Africa could be heard in Madrid and by early November elements of the Nationalist Army had reached the south-western suburbs. The Republican government was so convinced that Madrid would fall that, on 6 November, it left for Valencia, and placed the protection of the city in the hands of a military Junta de Defensa, under General Miaja.

However, helped by vital Russian military aid, the newly arrived 11th International Brigade and the Communist Party’s Fifth Regiment, the population of Madrid embarked on a desperate defence, spurred on by the defiant speeches of Dolores Ibarruri, La Pasionaria. There was desperate hand-to-hand fighting as Moroccan troops almost reached the city centre, but the defenders drove them back. By the end of November, the Nationalist attack was spent and the city, for the moment, held out.

The following month, in December, the rebels began an attempt to cut the Madrid-La Coruna road to the north-west of the capital. After heavy losses in fighting around the village of Boadilla del Monte, the attack was called off before, on January 5, the assault was renewed. During four days of fighting, for very little strategic gain by the rebels, each side lost in the region of 15,000 men. Casualties among the International Brigades were particularly high.

In February 1937 the rebels made a renewed attempt to surround Madrid by cutting the road to Valencia in the Jarama valley to the south of the Spanish capital. Republican troops reinforced by International Brigades, including British and Americans, were thrown in to the defence. Again the forces of the Republican Army held on desperately, allowing the rebels to make little progress and again the number of casualties was enormous. The Republicans lost perhaps 25,000 and the Nationalists 20,000.

On March 1, Franco agreed to a new two-pronged offensive to the east of the capital pressed upon him by Mussolini, flushed with the recent capture of Malaga by Italian forces. The plan involved an attack by Italian troops at Guadalajara, supported by Spanish forces moving on Alcala de Henares from Jarama. However, the Italians became bogged down by determined Republican resistance, aided by appalling weather conditions that prevented the rebel air-force from operating effectively. On March 12, the Republican forces, including Italian members of the International Brigades, launched a counter-attack. When the Nationalist offensive at Jarama failed to materialise, the Republicans routed the Italian forces. Mussolini responded furiously by declaring that Italian forces would remain in Spain until a Nationalist victory washed away the shame of their defeat at Guadalajara.

On March 1, Franco agreed to a new two-pronged offensive to the east of the capital pressed upon him by Mussolini, flushed with the recent capture of Malaga by Italian forces. The plan involved an attack by Italian troops at Guadalajara, supported by Spanish forces moving on Alcala de Henares from Jarama. However, the Italians became bogged down by determined Republican resistance, aided by appalling weather conditions that prevented the rebel air-force from operating effectively. On March 12, the Republican forces, including Italian members of the International Brigades, launched a counter-attack. When the Nationalist offensive at Jarama failed to materialise, the Republicans routed the Italian forces. Mussolini responded furiously by declaring that Italian forces would remain in Spain until a Nationalist victory washed away the shame of their defeat at Guadalajara.

With Nationalist efforts to capture Madrid essentially defeated, the war moved to the north of Spain as Franco attempted to overcome Basque forces who, despite their Catholic beliefs, had remained loyal to a Republic which offered a level of autonomy fervently opposed by the rebels. As the Nationalist forces gradually closed on the heavily fortified city of Bilbao, the rebels launched an air attack on the ancient Basque market town of Guernica. In one afternoon of bombing, the undefended wooden town was razed to the ground by the German Condor legion. Attempts by the Nationalists to deny responsibility for the atrocity were quickly and effectively shown to be false and the bombing of Guernica took on a central significance in the war, immortalised by the famous painting by Picasso.

In May 1937 cracks in the Republican Popular Front coalition became significantly wider, when what was essentially a civil war erupted in Barcelona. Despite the inclusion of four anarchists into the Republican government, contradictions between Republicans, moderate Socialists and Communists on one hand and the revolutionary proletarian groups on the other had remained a burning issue for the Republic. The immediate catalyst of the May events was the raid on the CNT-controlled central telephone exchange ordered on May 3 by the PSUC police commissioner for Catalonia. The CNT and the POUM fought on for several days until the CNT leadership, only too aware that the civil war could only help Franco, instructed its militants to lay down their arms. Under strong pressure from the Communists, the Republic then set about ensuring the complete destruction of the POUM. In the ensuing crackdown the POUM leader, Andres Nin, was arrested and later murdered by the NKVD. Others members, including George Orwell, prudently went into hiding. The POUM was banned in June 1937, and moves were made to suppress the collectives and re-impose centralised government. By 1938 little of the autonomy granted by the Popular Front would remain

In May 1937 cracks in the Republican Popular Front coalition became significantly wider, when what was essentially a civil war erupted in Barcelona. Despite the inclusion of four anarchists into the Republican government, contradictions between Republicans, moderate Socialists and Communists on one hand and the revolutionary proletarian groups on the other had remained a burning issue for the Republic. The immediate catalyst of the May events was the raid on the CNT-controlled central telephone exchange ordered on May 3 by the PSUC police commissioner for Catalonia. The CNT and the POUM fought on for several days until the CNT leadership, only too aware that the civil war could only help Franco, instructed its militants to lay down their arms. Under strong pressure from the Communists, the Republic then set about ensuring the complete destruction of the POUM. In the ensuing crackdown the POUM leader, Andres Nin, was arrested and later murdered by the NKVD. Others members, including George Orwell, prudently went into hiding. The POUM was banned in June 1937, and moves were made to suppress the collectives and re-impose centralised government. By 1938 little of the autonomy granted by the Popular Front would remain

The following month, in June 1937, Bilbao fell to the advancing Nationalist forces. The Republic responded by launching a major offensive at Brunete on July 6, designed to relieve pressure on the northern front and break through the rebels at their weakest point to the west of Madrid. However, despite initial Republican gains, Franco was able to bring his superior numbers to bear and gradually pushed back the republican forces.

With the failure of the Brunete offensive, Franco was able to continue with his northern offensive, and Santander fell to the rebels at the end of August. Again the Republicans tried to divert attention from the northern front by launching an offensive in Aragon aimed at capturing Saragossa. Though inroads into Aragon were made- International Brigades were heavily involved in capturing Quinto and Belchite despite heavy casualties- Saragossa remained in rebel hands, and the rest of the Basque regions and Asturias fell to the rebels by October 1937. The loss of the northern ports and the vital heavy industries was a crucial blow to the Republic.

With the failure of the Brunete offensive, Franco was able to continue with his northern offensive, and Santander fell to the rebels at the end of August. Again the Republicans tried to divert attention from the northern front by launching an offensive in Aragon aimed at capturing Saragossa. Though inroads into Aragon were made- International Brigades were heavily involved in capturing Quinto and Belchite despite heavy casualties- Saragossa remained in rebel hands, and the rest of the Basque regions and Asturias fell to the rebels by October 1937. The loss of the northern ports and the vital heavy industries was a crucial blow to the Republic.

Despite these losses the Republic launched a surprise attack in December 1937 and captured Teruel. In freezing winter conditions the Republic’s best troops, including the International Brigades and the Communist 5th Regiment, fought desperately, but outnumbered, they were unable to prevent Franco bringing his superior numbers of arms and men to bear. The Nationalists recaptured Teruel in February 1938.

The following month, on March 7, 1938, Franco launched a massive and well-prepared attack in Aragon involving 100,000 men, 200 tanks and over 600 Italian and German planes. What began as a series of break-throughs for the Nationalists swiftly became outright retreat for the exhausted Republican forces, as their lines virtually collapsed under the ferocious and well-supplied offensive. By April 15, the rebels had reached the Mediterranean and cut the Republic in two, and by the end of the month the rebels held a fifty-mile stretch of coast. Had Franco headed north into Catalonia he would probably have ended the war a year earlier than he did. However, Franco’s aim was not to defeat the Republic, but to annihilate it forever.

The following month, on March 7, 1938, Franco launched a massive and well-prepared attack in Aragon involving 100,000 men, 200 tanks and over 600 Italian and German planes. What began as a series of break-throughs for the Nationalists swiftly became outright retreat for the exhausted Republican forces, as their lines virtually collapsed under the ferocious and well-supplied offensive. By April 15, the rebels had reached the Mediterranean and cut the Republic in two, and by the end of the month the rebels held a fifty-mile stretch of coast. Had Franco headed north into Catalonia he would probably have ended the war a year earlier than he did. However, Franco’s aim was not to defeat the Republic, but to annihilate it forever.

Three months later, in July 1938, the Republic launched what would become their last act when Republican forces advanced back across the River Ebro. A special Army of the Ebro was formed for the offensive, which was placed under the command of the Communist General Juan Modesto. But, as had happened too many times for the Republic, initial successes soon ground to a halt when faced with the nationalists’ hugely superior numbers and armaments. The battle of the Ebro lasted for over three months until, bled to death, the Republican Army collapsed.

Meanwhile, events outside Spain had effectively sealed the Republic’s fate when Czechoslovakia had been essentially “surrendered” to the Nazis at the Munich Agreement of September 29, 1938. Spanish premier Negrín’s hopes of assistance from the western democracies were dashed but, nevertheless, Juan Negrín withdrew the International Brigades in October, gambling that pressure would be put on Franco to respond in kind, by sending back German and Italian troops. But it was too late. Supplied with fresh armaments from Germany, Franco’s offensive of November 1938 sounded the death knell for the Republic and, by January, Franco had captured Barcelona.

Meanwhile, events outside Spain had effectively sealed the Republic’s fate when Czechoslovakia had been essentially “surrendered” to the Nazis at the Munich Agreement of September 29, 1938. Spanish premier Negrín’s hopes of assistance from the western democracies were dashed but, nevertheless, Juan Negrín withdrew the International Brigades in October, gambling that pressure would be put on Franco to respond in kind, by sending back German and Italian troops. But it was too late. Supplied with fresh armaments from Germany, Franco’s offensive of November 1938 sounded the death knell for the Republic and, by January, Franco had captured Barcelona.

On March 4, Colonel Casado, commander of the Republican Army of the Centre, launched a revolt in Madrid in an attempt to bring the war to an end. The revolt against the Republican government sparked off the second civil war in the Republican zone as Casado’s forces battled with Communists who were determined to fight on. Over 200 were killed before Casado’s forces gained control and an attempt was made to negotiate peace with Franco. However, Franco refused to negotiate and instead, on March 26, launched a gigantic and virtually unopposed Nationalist advance along a wide front. The following day Nationalists entered Madrid and, by March 31, 1939, all of Spain was in Nationalist hands. On April 1, 1939 Franco announced that the Spanish Civil War was officially at an end.

Refugees and Internment

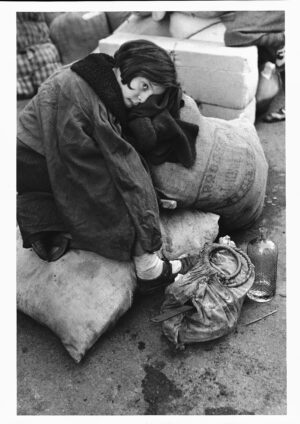

Following the fall of Barcelona in January 1939, a flood of desperate civilians including women and children flowed north towards France. Behind them came the retreating Republican Army covered by a rearguard composed of the Durruti Column and elements of the Army of the Ebro. Despite protests from the right wing press in France, the border was opened to admit them into France, where they were interned in concentration camps at Gurs, Argeles-sur-mer, Barcares and St. Cyprien. Conditions inside the camps were desperate, with shelter, supplies and medical care virtually non-existent. Strict military discipline prevailed, and those suspected to be Communists and Anarchists were taken to separate prison camps where they were held as prisoners under a regime of hard labor.

Following the fall of Barcelona in January 1939, a flood of desperate civilians including women and children flowed north towards France. Behind them came the retreating Republican Army covered by a rearguard composed of the Durruti Column and elements of the Army of the Ebro. Despite protests from the right wing press in France, the border was opened to admit them into France, where they were interned in concentration camps at Gurs, Argeles-sur-mer, Barcares and St. Cyprien. Conditions inside the camps were desperate, with shelter, supplies and medical care virtually non-existent. Strict military discipline prevailed, and those suspected to be Communists and Anarchists were taken to separate prison camps where they were held as prisoners under a regime of hard labor.

From April 1939 the Spanish Republican exiles were allowed option to leave the camps, provided they obtained work with local employers or enlisted in labour battalions, the Foreign Legion or the French Army. Around 15,000 joined the Foreign Legion, including the elements of the Durruti column who were offered a choice between this and forced repatriation.

Following the fall of France in 1940 over 220,000 Spaniards were engaged in forced labor for French and German enterprises in France.

International Brigaders and Spaniards in the Second World War

Many of the International Brigaders from around the world continued their fight against fascism during the Second World War, though until the invasion of the USSR in 1941 official Communist Party policy was to regard the conflict as an imperialist war. And as ‘premature anti-fascists’, ex-brigadistas were not always admitted into the regular armed forces, despite their combat experience. Despite this, many served with distinction in the allied forces throughout the war in a wide variety of roles.

Many Spanish Republicans fought with the French army until France fell in July 1940. Of these, over 6,000 died and between 10,000 and 14,000 were taken prisoner when the Germans defeated France. Captured Spaniards were not treated as prisoners of war but sent to concentration camps, usually Mauthausen. As many as 30 000 Spanish refugees were deported from France to Germany, perhaps half of whom ended up in Nazi concentration camps.

During the course of the war thousands of Spanish Republicans fought with the allies in various theatres and a number fought in the Red Army and Soviet Air Force. A number of Basques fought in the Pacific with the US Army. Over 60,000 Spanish exiles fought with the French Resistance and more than 4,000 Spaniards took part in the Maquis uprising in Paris that began on August 21st 1944. Spanish Republicans were able to rejoice in a moment of triumphant when the vehicles of the first units to liberate Paris carried Spanish Republican flags and bore the names Ebro, Madrid, Teruel and Guadalajara.

In total during the Second World War, 25,000 Spaniards died in concentration camps or fighting in armed units.