By: Cary Nelson

“Barcelona beautiful. Streets aflame with posters of all parties for all causes, some of them put out by combinations of parties.”

– Robert Merriman

Introduction

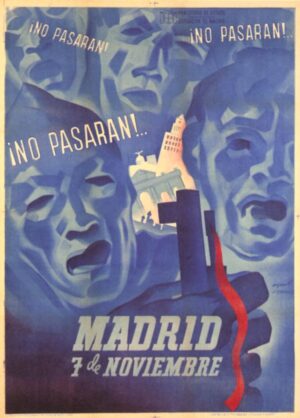

Picture yourself one moonlit night in Madrid late in 1936. Visibility is good, so the fascist bombers are out in force. Germany’s Adolph Hitler has provided his Condor Legion to help General Francisco Franco bomb his own capital city into submission. As the residents of Barcelona would also come to learn in the course of the war, five hundred pound bombs are a serious weapon; they burrow deep into a building before exploding. Meanwhile, at the city’s edge, high on Mount Garabitas above the wooded hills of the Casa de Campo, Franco’s soldiers have set the sights of their artillery pieces on the city’s landmarks. The Telephonica building gives them a range finder and a line of sight.

Picture yourself one moonlit night in Madrid late in 1936. Visibility is good, so the fascist bombers are out in force. Germany’s Adolph Hitler has provided his Condor Legion to help General Francisco Franco bomb his own capital city into submission. As the residents of Barcelona would also come to learn in the course of the war, five hundred pound bombs are a serious weapon; they burrow deep into a building before exploding. Meanwhile, at the city’s edge, high on Mount Garabitas above the wooded hills of the Casa de Campo, Franco’s soldiers have set the sights of their artillery pieces on the city’s landmarks. The Telephonica building gives them a range finder and a line of sight.

When the air raid siren sounds you seek out the nearby subway refugio. There, as people gather together amidst repeated detonations, powerless, unable to strike back, the bright colors of the posters on the subway walls remind you that elsewhere your comrades are striking back. And they remind you that the city’s anguish is at once exemplary and exceptional, that it is the object of the world’s attention. Later, when the sun rises over smoking ruins, it brightens the bold colors of resistance and solidarity on posters covering walls still standing. Madrid is of one mind; these posters are its hues and its icons, the forms in which it knows itself.

The Spanish Civil War Poster

JAN. 7. Barcelona beautiful. Streets aflame with posters of all parties for all causes, some of them put out by combinations of parties.

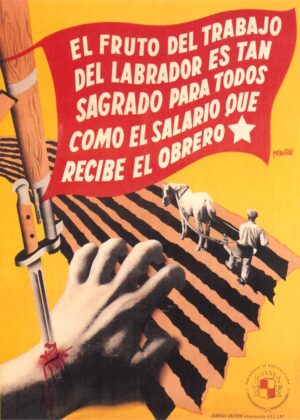

So wrote American volunteer Robert Merriman in his diary when he arrived in Spain at the beginning of 1937. Spain’s foreign minister Alvarez del Vayo was still more eloquent in his 1940 memoir. Full-color posters, banners, and fliers, brandishing dramatic swaths of red and black or blue or yellow were all over the city: along the streets, taped to windows, tacked up on kiosks in every public square, on the interior walls of office buildings and private homes, in all the subway stations, on the sides of buses, trucks, and even trains. By the second week of the war, early in July 1936, they were already defining the public space of major cities. Daily Worker correspondent George Marion, writing to Time magazine on his return home — his March 1, 1938, letter is unpublished but a copy is in his file at the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives — reported that “the posters flow from a hundred sources. During the many months I was in Spain I found the collection of posters just about a full-time job because there was no central source.” Many, he continued, were “put out by non-governmental bodies: trade unions, youth organizations, women’s committee, Fifth Regiment, and others.” On the Puerto del Sol, central square of Madrid, one hugh poster on the side of a building occupied a whole floor. Soon they appeared on bulletin boards and at headquarters at the fronts where men were fighting. They gave people information they needed, built morale, and focused debate and action on the key issues and campaigns of a given week. Communication, exhortation, persuasion, instruction, celebration, warning: all these aims and more were served by the 1,500 to 2,000 different posters appearing in the Spanish Republic from 1936-38. Of this number, perhaps 20 percent were exclusively textual; the rest of the posters were preeminently pictorial.

They were first of all an excellent mode of communication for a population with a high rate of illiteracy. For many years, Spain’s Catholic church, in control of public education, believed there was no need for either peasants or women to read. The Republic would begin rapidly to reverse that pattern, but in the meantime posters in public places combining striking iconography with brief slogans made it possible to get basic messages out to people quickly. The combination of strong graphics with concise captions also made the posters memorable and convincing.

They were first of all an excellent mode of communication for a population with a high rate of illiteracy. For many years, Spain’s Catholic church, in control of public education, believed there was no need for either peasants or women to read. The Republic would begin rapidly to reverse that pattern, but in the meantime posters in public places combining striking iconography with brief slogans made it possible to get basic messages out to people quickly. The combination of strong graphics with concise captions also made the posters memorable and convincing.

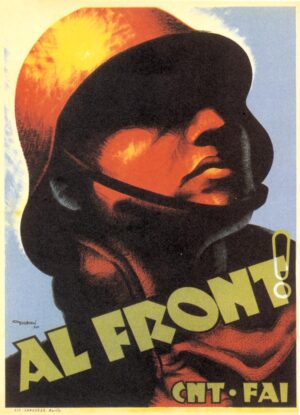

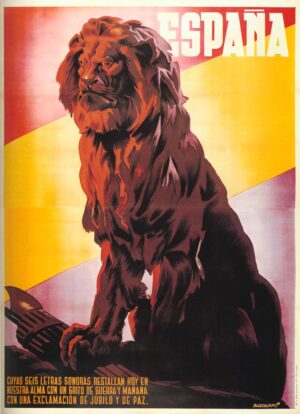

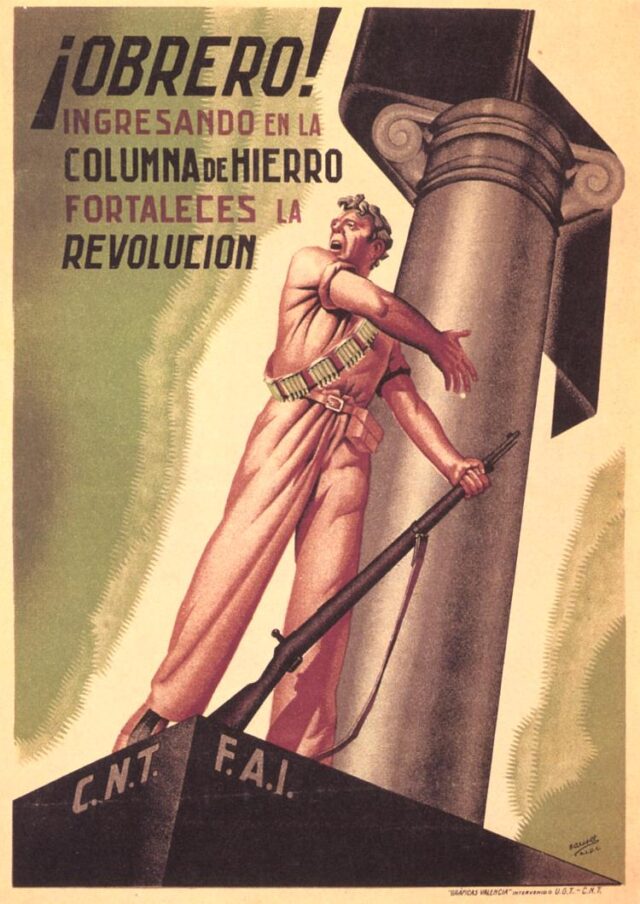

Early on large numbers of them were essentially recruitment posters. Carles Fontsere’s Al Front urged everyone to turn their eyes and their full attention to the rapidly expanding war; its helmeted soldier negotiated all the extremes of light and dark in such a way as to suggest there was no world outside the imperiled horizon of battle. In the presence of this icon there might seem no alternative but to volunteer. So too with Jose Bardasano’s España. All available and politically relevant nobility is combined in its lion’s confident stance and gaze of warm concern; stand with honor, the poster urges us, and give yourself over to be gathered into the country’s protective vigilance. These highly general inducements to solidarity and commitment were balanced with special pleas for particular militias. “Workers!” declared one of J. Bauset’s posters, “joining the Iron Column fortifies the revolution.” The iron column was an anarchist battalion, but other militias had their recruitment posters as well. In such cases, moreover, the posters went beyond literal recruitment. They amounted to ideological recruitment, urging people to place their faith and their loyalty with a particular political point of view. About some poster artists little is known, but basic biographical informations does exist for several, including Bardasano, Fontsere, Francisca, Puyol, Renau, and Sim — who are unquestionably among the most important poster artists of the war.

Early on large numbers of them were essentially recruitment posters. Carles Fontsere’s Al Front urged everyone to turn their eyes and their full attention to the rapidly expanding war; its helmeted soldier negotiated all the extremes of light and dark in such a way as to suggest there was no world outside the imperiled horizon of battle. In the presence of this icon there might seem no alternative but to volunteer. So too with Jose Bardasano’s España. All available and politically relevant nobility is combined in its lion’s confident stance and gaze of warm concern; stand with honor, the poster urges us, and give yourself over to be gathered into the country’s protective vigilance. These highly general inducements to solidarity and commitment were balanced with special pleas for particular militias. “Workers!” declared one of J. Bauset’s posters, “joining the Iron Column fortifies the revolution.” The iron column was an anarchist battalion, but other militias had their recruitment posters as well. In such cases, moreover, the posters went beyond literal recruitment. They amounted to ideological recruitment, urging people to place their faith and their loyalty with a particular political point of view. About some poster artists little is known, but basic biographical informations does exist for several, including Bardasano, Fontsere, Francisca, Puyol, Renau, and Sim — who are unquestionably among the most important poster artists of the war.

Women in Posters

4 R

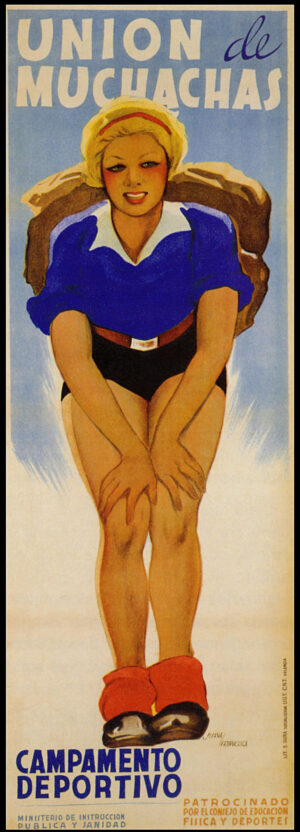

The Spanish Civil War accelerated a radical transformation in the status of women in the Republic. Women took up work in the factories; they had wide access to education for the first time; their legal status was secured; women’s organizations and cultural journals were founded; abortion was legalized; and, most surprisingly from the viewpoint of the rest of the world, women fought in the front lines in the opening months of the war.

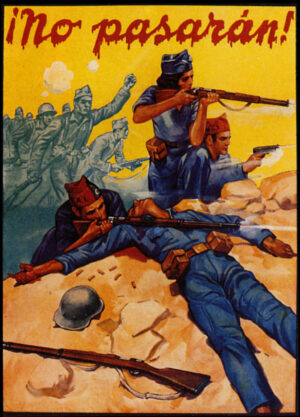

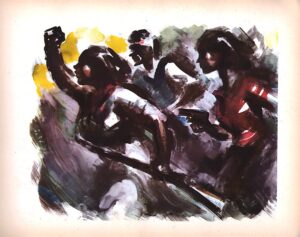

The first months of the war also saw a series of gendered posters. Spanish women were urged to join the militias, to take up arms with men and boys. Even now, these images, including Sim’s remarkable portraits of armed women in battle, have the power to surprise us. Sim’s images of armed women striding forward purposefully in battle are still striking and unconventional, even after sixty years. But the series of prints actually plays havoc with gender stereotypes in a variety of ways. The captions to Battering Ram and Rest are gender neutral, and the prints depict men and women as equals. The captions to She Saw Him Fall (at left) and She Knew How to Die substitute female pronouns in rhetoric more familiar from paeans to male heroism

and resolve and thus demolish the notion that these traits are gender specific. The captions to Youth and They Shall Not Pass, on the other hand, are partly inflected to account for their gendered subject. Most conventional of all, of course, is Delirium, which shows a  nurse ministering to a feverish soldier. But there are several prints in the series devoted to the medical services, and one, In the Thick of the Fight, shows a militiaman and a nurse carrying a wounded figure from a battle in progress; the gender neutral caption describes them both as “symbols of the revolution . . . muscles taut and a spark of rebelliousness in their hearts.” Of the thirty-one prints in the series (plus one on the cover), all executed in 1936 and not all depicting people, fifteen of them have women as their sole or equal subject. Sim’s Estampas de la Revolucion Espanola 19 Julio de 1936 was published in Barcelona by the propaganda offices of the CNT/FAI.

nurse ministering to a feverish soldier. But there are several prints in the series devoted to the medical services, and one, In the Thick of the Fight, shows a militiaman and a nurse carrying a wounded figure from a battle in progress; the gender neutral caption describes them both as “symbols of the revolution . . . muscles taut and a spark of rebelliousness in their hearts.” Of the thirty-one prints in the series (plus one on the cover), all executed in 1936 and not all depicting people, fifteen of them have women as their sole or equal subject. Sim’s Estampas de la Revolucion Espanola 19 Julio de 1936 was published in Barcelona by the propaganda offices of the CNT/FAI.

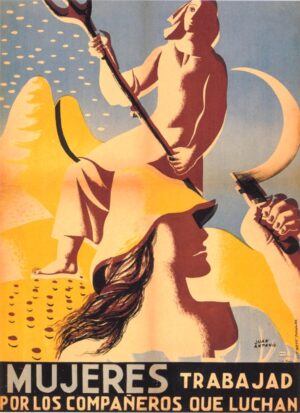

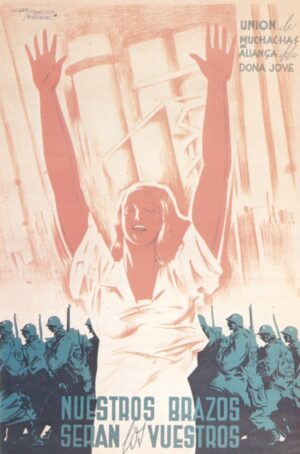

By spring 1937, however, it became clear to many that the militias would not suffice to fight large-scale battles in a prolonged war; a centrally organized army was required to meet coordinated attacks by columns of infantry, tanks, and planes. Meanwhile, the army needed to increase its size as well, thereby leaving behind fewer men to keep Spain’s industries running. Women were not sent back to the home, their traditional site in Spain, but they disappeared from combat as the militias were dissolved; instead, posters appearing from mid-1937 on urged them to take up the slack in industry and agriculture. Juan Antonio’s Women, Work for the Comrades Who Fight (at right) is a good example of that sort of poster, as is a poster jointly designed by Juana Francisca and Jose Bardasano, Our Arms wll be Yours (below).

By spring 1937, however, it became clear to many that the militias would not suffice to fight large-scale battles in a prolonged war; a centrally organized army was required to meet coordinated attacks by columns of infantry, tanks, and planes. Meanwhile, the army needed to increase its size as well, thereby leaving behind fewer men to keep Spain’s industries running. Women were not sent back to the home, their traditional site in Spain, but they disappeared from combat as the militias were dissolved; instead, posters appearing from mid-1937 on urged them to take up the slack in industry and agriculture. Juan Antonio’s Women, Work for the Comrades Who Fight (at right) is a good example of that sort of poster, as is a poster jointly designed by Juana Francisca and Jose Bardasano, Our Arms wll be Yours (below).

One of the most telling pieces of visual evidence of the disappearance of women from combat is Sim’s second portfolio of drawings, 12 Escenas de Guerra. In his first collection of battle illustrations, Estampas de la Revolucion Espanola 19 Julio de 1936, women are portrayed in about half of the illustrations; 12 Escenas de Guerra is devoted entirely to men. His first portfolio, notably, was published by the anarchists. The second collection was issued by the central government, the Generalitat, of Catalonia. The second collection also uses less vibrant color, emphasizing the brown uniforms of the regular army rather than the red and black colors of anarchism.

One of the most telling pieces of visual evidence of the disappearance of women from combat is Sim’s second portfolio of drawings, 12 Escenas de Guerra. In his first collection of battle illustrations, Estampas de la Revolucion Espanola 19 Julio de 1936, women are portrayed in about half of the illustrations; 12 Escenas de Guerra is devoted entirely to men. His first portfolio, notably, was published by the anarchists. The second collection was issued by the central government, the Generalitat, of Catalonia. The second collection also uses less vibrant color, emphasizing the brown uniforms of the regular army rather than the red and black colors of anarchism.

How Posters were Produced

Our information about production methods for Spanish Civil War posters comes mainly from Carles Fontsere, the Catalan artist who was active in the Union of Professional Artists (Sindicato de Dibujantes Profesionales) in Barcelona. As he describes the process, a poster artist typically painted in water colors on moistened paper stretched across a frame. The verbal text was also painted by hand. In most cases, after the original poster was painted, a lithographer copied each color onto a separate zinc plate for printing. Some of the artists, however, including Fontsere, worked directly on the zinc plates themselves. The requirement for multiple plates worked against the use of too many colors; three or four was typical, five or six unusual.

A number of other material constraints also affected the posters. First, they had to be clearly visible from a distance in order to be effective in public sites, including outdoor locations. Second, the use of water colors made it impractical to overpaint with light colors over dark ones. Instead, poster artists often used the white of the paper itself as a major design element. Finally, the paper used was generally the least expensive, often a form of newsprint. The largest number of posters were about 30 inches wide and forty inches high, though double-sized posters, printed on two sheets of this size and glued together were not uncommon, and some substantially larger posters were produced. Many posters were printed in runs of 5,000 or 10,000 copies, enough to guarantee wide distribution and visibility. The cities of Barcelona, Madrid, and Valencia each had two or more large poster workshops working continually. Usually a given workshop specialized in posters for a particular political group or coalition of groups.

Variations on the primary pattern included a number of small posters printed by photo-chromolithography on high quality paper and sold in streetside stalls, offices, and bookstores. Drawings and lithographs were also issued in more limited editions on heavy stock for sale to individual buyers. And some posters needed for immediate use in a particular place were done as unique paintings, sometimes in oil. Like similar workshops in Madrid and Valencia, the Sindicato also produced banners and placards. The banners were painted directly on primed cotton whenever it could be obtained.

A great many posters were also reprinted as postcards, sometimes many months later, so that a given image often received a second life and a second means of distribution. A considerable number of postcards were also independently designed and never appeared as posters. From time to time sets of ten postcards were sold in illustrated packets. Many thousands of such cards were sent home by international soldiers, journalists, and other visitors to Spain. Finally, small decorative stamps in substantial numbers over a thousand different ones during the course of the war’s were issued as miniature posters. Some reproduced large poster designs, but many represent independent works of art.

Fontsere has called the posters the “certificate” of the social revolution that formed in response to the generals’ attempted coup: “each union, each small committee, came out with its poster; each profession, each trade – barbers, taxi drivers, tram conductors – could be seen in a poster breaking the bonds that oppressed them.”

The International Response

Inevitably, visitors and volunteers began sending the posters home; there was no more economical way to communicate the passion of the war. Here, on a single sheet typically thirty inches wide and forty high, was a powerful synecdoche for the war’s anguish and its idealism – a woman holding a murdered child, the working classes looking up as they yearned for liberation, the archetypal soldier now taking a stand against the evil of fascism. Inevitably too, not only in Spain but across Europe and in America as well, exhibitions were mounted to give people a chance to see numbers of posters at once. Few at the time doubted that art and politics were here decisively fused, for the posters were both aesthetically beautiful or terrifying and politically compelling. They cried out to be seen and acted upon; between the two impulses no space of doubt need fall. If we have unlearned this lesson in the intervening years, now seems an appropriate occasion to have it displayed for a different generation.

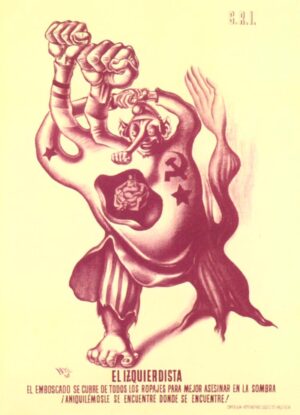

When American volunteers wrote home about the posters they saw and sometimes sent back to friends and family, it was, often as not, an individual poster that would engage their attention. Leon Rosenthal, writing home in August 1937, took some relish in comparing a friend back home to one of Ramon Puyol’s satiric portraits, The Ultraleftist / El Izquierdista (at left): “As for Gershon – I wish I had the poster I would like to send him – it shows the super-leftist – with two arms on the right shoulder raised in 2 fists and one left one – and a fist for a nose…and inside his belly is a fat bourgeois sitting on a soft chair & smoking a cigar.”

When American volunteers wrote home about the posters they saw and sometimes sent back to friends and family, it was, often as not, an individual poster that would engage their attention. Leon Rosenthal, writing home in August 1937, took some relish in comparing a friend back home to one of Ramon Puyol’s satiric portraits, The Ultraleftist / El Izquierdista (at left): “As for Gershon – I wish I had the poster I would like to send him – it shows the super-leftist – with two arms on the right shoulder raised in 2 fists and one left one – and a fist for a nose…and inside his belly is a fat bourgeois sitting on a soft chair & smoking a cigar.”

Dave Gordon, writing in July 1938, concentrated on a poster with little dramatic color but with a decisive cultural message:

Who hasn’t seen thousands of posters, whether for advertising or for propaganda? (Of course the advertising is only another type of propaganda itself.) Has there ever been a poster which did not contain a rather more than less obvious moral tailing along, either in the watchwords or catchwords or in the photograph, or drawing? It would be hard to find one which spoke for itself. It is extremely difficult to present the lesson desired without some concise wording or without plainly indicating the idea graphically.

Yet this is exactly what was done in a poster issued by the Generalitat of Catalonia. What is more, this particular poster deals with the principal pride of Catalonia, with what so strongly characterizes its special individuality and comprehends all of its cultural traits — the Catalan language.

Picture to yourself a photo-montage of two pages of a newspaper, one more and the other less obliquely reproduced on a huge poster sheet. Remember, too, that these newspaper pages are taken from a rebel fascist newspaper, impertinently bearing the name Unidad. The name “Catalonia” is printed in large letters, once at the head and once at the foot of the poster. Part of one of the newspapers is underscored in black. The underscored lines are only one sentence in a longer article. The paper is written in the Castilian tongue. The specially marked portion, translated, reads: “Jose Juan Jubert (fined) 100 pesetas and Javier Gibert Porrero, 100 pesetas, for speaking in Catalan at the table in the dining room of a hotel.” The newspaper, published in San Sebastian, bears the date January 6, 1938. The news item is a report of the court procedure of a day at the fascist tribunals.

The poster carries no more than what I have explained above. Yet it speaks worlds. It reflects a profound confidence in the understanding and pride of the Catalan. At the same time it reveals a grand contempt for the dogs of fascism who aim to crush the culture of the regions of Spain. It is a convincing call to all Catalonia to fight with Spain to defeat fascism if it wishes to retain its freedoms.

It is a simple poster, colored simply. I wish I had a copy to send you so that I need not have been compelled to describe it in words. It speaks most eloquently for itself. Yet I can’t help writing about it for two reasons — it impressed me considerably and I could not get a copy of it.

Poster Campaigns

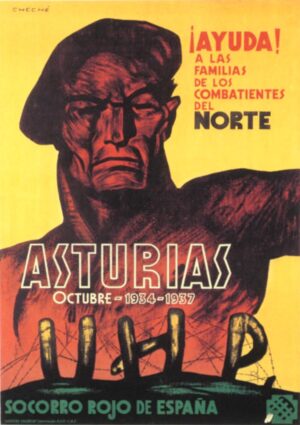

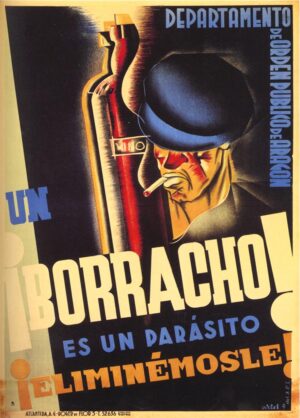

Throughout the war there were poster campaigns focused on particular needs and events. Thus when the Asturias were overrun by Franco’s troops posters like Cheche’s Aid the Families of the Fighters of the North (at left) helped focus public attention on the plight of the refugees. Continuing problems, like the perennial one of soldiers getting drunk on leave, would also be the focus of special publicity campaigns; hence Artel’s A Drunk! He is a parasite! Eliminate him! (right). Some issues and campaigns were the subject of posters throughout the war; the effort to promote literacy, one of the Republic’s key social agendas, was one of these. Other topics received more intermittent treatment; these include ecological posters warning people cutting wood for heat about the dangers of deforestation. The last year of the war, when the Republic was losing territory to the fascists, saw a number of posters aiming to help build morale, stiffen resistance, and reinforce solidarity. Slogans like “Resist,” “Counterattack,” or “Fortify” identify a poster as produced in 1938 rather than 1937.

Throughout the war there were poster campaigns focused on particular needs and events. Thus when the Asturias were overrun by Franco’s troops posters like Cheche’s Aid the Families of the Fighters of the North (at left) helped focus public attention on the plight of the refugees. Continuing problems, like the perennial one of soldiers getting drunk on leave, would also be the focus of special publicity campaigns; hence Artel’s A Drunk! He is a parasite! Eliminate him! (right). Some issues and campaigns were the subject of posters throughout the war; the effort to promote literacy, one of the Republic’s key social agendas, was one of these. Other topics received more intermittent treatment; these include ecological posters warning people cutting wood for heat about the dangers of deforestation. The last year of the war, when the Republic was losing territory to the fascists, saw a number of posters aiming to help build morale, stiffen resistance, and reinforce solidarity. Slogans like “Resist,” “Counterattack,” or “Fortify” identify a poster as produced in 1938 rather than 1937.

There were new posters continually throughout the war and in time old ones would disappear from stores and be covered over on the streets with new issues. One of the most useful things to know would be the exact week that each poster was published. Definite proof would not always be available, but a search through daily newspapers and weekly magazines from 1936-39 could produce a list of poster reproductions; that would set latest dates of appearance for a number of posters. Also helpful would be a detailed chronology of wartime slogans and cultural campaigns; that would give likely dates for many of the posters bearing such slogans. Though there are many detailed military and political chronologies of the war, we lack a comparably detailed cultural chronology. Again, no one has yet done this research in Spanish publications, but it could be done. All this would enable far more precise readings of the posters than scholars have produced to date.

There were new posters continually throughout the war and in time old ones would disappear from stores and be covered over on the streets with new issues. One of the most useful things to know would be the exact week that each poster was published. Definite proof would not always be available, but a search through daily newspapers and weekly magazines from 1936-39 could produce a list of poster reproductions; that would set latest dates of appearance for a number of posters. Also helpful would be a detailed chronology of wartime slogans and cultural campaigns; that would give likely dates for many of the posters bearing such slogans. Though there are many detailed military and political chronologies of the war, we lack a comparably detailed cultural chronology. Again, no one has yet done this research in Spanish publications, but it could be done. All this would enable far more precise readings of the posters than scholars have produced to date.

Even without being able to date and contextualize each poster, we can, however, give some overall feeling for the rich, mutually reinforcing semiotic environment in which many of the posters were displayed. Those that were published and displayed for particular week-long campaigns, for example, would have seemed not isolated objects to be noticed or ignored but rather part of city-wide activities and celebrations concentrated on a single topic. Thus a week-long campaign to build support for the Republic’s new regular army was held throughout loyalist Spain in February 1937. Numerous posters were created for the occasion and displayed all along the streets. In Barcelona’s Plaza de Catalunya a huge soldier designed by sculptor Miguel Paredes was constructed of wood, wire, and plaster of Paris. At the week’s end a parade was held; as the army marched through Barcelona’s Paseo de Gracia and Plaza de Catalunya, literally tens of thousands of volunteers held posters and placards aloft. Meanwhile numerous pamphlets and postcards were printed to supplement the posters, along with smaller decorations that people could attach to their clothing.

Even without being able to date and contextualize each poster, we can, however, give some overall feeling for the rich, mutually reinforcing semiotic environment in which many of the posters were displayed. Those that were published and displayed for particular week-long campaigns, for example, would have seemed not isolated objects to be noticed or ignored but rather part of city-wide activities and celebrations concentrated on a single topic. Thus a week-long campaign to build support for the Republic’s new regular army was held throughout loyalist Spain in February 1937. Numerous posters were created for the occasion and displayed all along the streets. In Barcelona’s Plaza de Catalunya a huge soldier designed by sculptor Miguel Paredes was constructed of wood, wire, and plaster of Paris. At the week’s end a parade was held; as the army marched through Barcelona’s Paseo de Gracia and Plaza de Catalunya, literally tens of thousands of volunteers held posters and placards aloft. Meanwhile numerous pamphlets and postcards were printed to supplement the posters, along with smaller decorations that people could attach to their clothing.

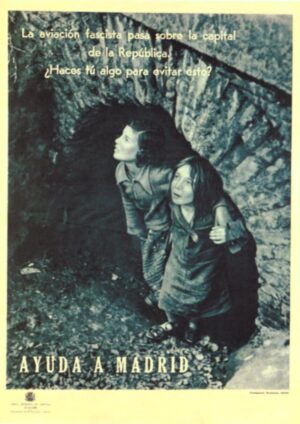

Large multifaceted cultural events focused on other week-long campaigns as well. A week of support for the Basque region, held from May 29 to June 6, 1937, brought out posters, banners, and placards with Basque motifs. A monument symbolizing the sacred tree of Guernica was erected in the Plaza de Catalunya, and the Basque play Pedro Mari was performed in the Liceo theater on Barcelona’s Ramblas; poster artists designed the sets. The opening performance was interrupted by a bombing raid, but the cast and audience spurned the air raid shelters and stayed on singing the “Internationale.” Later that summer a week advocating Aid to Madrid (at left) followed. That fall special celebrations to honor the International Brigades were held in Madrid. On September 5 a mass meeting adorned with posters and banners produced for the occasion was held in the Monumental Cinema. Posters advertising the meeting and other posters honoring the I.B. went up across the city. Pamphlets were issued about the event, as was a book of poems about the volunteer soldiers.

Large multifaceted cultural events focused on other week-long campaigns as well. A week of support for the Basque region, held from May 29 to June 6, 1937, brought out posters, banners, and placards with Basque motifs. A monument symbolizing the sacred tree of Guernica was erected in the Plaza de Catalunya, and the Basque play Pedro Mari was performed in the Liceo theater on Barcelona’s Ramblas; poster artists designed the sets. The opening performance was interrupted by a bombing raid, but the cast and audience spurned the air raid shelters and stayed on singing the “Internationale.” Later that summer a week advocating Aid to Madrid (at left) followed. That fall special celebrations to honor the International Brigades were held in Madrid. On September 5 a mass meeting adorned with posters and banners produced for the occasion was held in the Monumental Cinema. Posters advertising the meeting and other posters honoring the I.B. went up across the city. Pamphlets were issued about the event, as was a book of poems about the volunteer soldiers.

Additional Resources

Online exhibits

Biblioteca Nacional de España, Biblioteca Digital Hispanica

Exhibit of Spanish Civil War posters

Bibliography

Julio Alvarez del Vayo, Freedom’s Battle, trans. Eileen E. Brooke (New York: Knopf, 1940).

Santiago Carrillo, Bardasano, su obra (Mexico: M. Leon Sanchez, 1943).

Peter N. Carroll, The Odyssey of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade: Americans In the Spanish Civil War (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1994).

Nicholas Chapman, Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Posters of the Spanish Civil War (Berkeley: Unpublished undergraduate honors’ thesis, University of California at Berkeley, 1993).

Joan Fontcuberta, Josep Renau: Fotomontador (Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Economica, 1984).

Carles Fontsere: Roma Paris Londres 1960 (Barcelona: Fundacio Caixa de Pensions, 1984).

Carles Fontsere, “Catalan Posters of the Spanish Civil War.” In Rupert Martin and Frances Morris, eds. No Pasaran! — Photographs and Posters of the Spanish Civil War (Bristol: Arnolfini Gallery, 1986).

Carles Fontsere, “El Sindicato de Dibujantes Profesionales.” In Joseph Temes, ed. Carteles de la Republica y de la Guerra Civil.

Nigel Glendinning, “Art and the Spanish Civil War.” In Stephen M. Hart, ed. “No Pasaran!: Art, Literature and the Spanish Civil War (London: Tamesis Books, 1988).

Carmen Grimau, El Cartel Republicano en la Guerra Civil (Madrid: Ediciones Catedra, 1979).

Javier Gomez Lopez, ed. Catalogo de Carteles de la Republica y la Guerra Civil Espanolas en la Biblioteca Nacional (Madrid: Ministry of Culture, 1990).

Luis Maria Caruncho Amat and Carlina Pena Bardasano, eds. Bardasano (1910-1979) (Madrid: Artes Graficas Municipales, 1986).

Cary Nelson and Jefferson Hendricks, eds. Madrid 1937: Letters of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade from the Spanish Civil War (New York: Routledge, 1996).

Josep Renau, Fata Morgana USA: The American Way of Life (Valencia: Museum of Photographic Arts, 1991).

Josep Renau, Funcion social del cartel (Valencia: Fernando Torres, 1976).

Josefina Servan Corchero and Antonio Trinidad Munoz, “Las mujeres en la cartelÃÂstica de la Guerra Civil.” In Las mujeres y la Guerra Civil Espanola (Salamanca: Ministry of Culture, 1991).

Manfred Schmidt, ed. Josep Renau: Grafik und Fotomontagen (East Berlin: Staatlicher Kunsthandel der DDR, 1981).

Josep Temes, ed. Carteles de la Republica y de la Guerra Civil (Barcelona: La Gaya Ciencia, 1978).

John Tisa, The Palette and the Flame: Posters of the Spanish Civil War (New York: International Publishers, 1979).

Kathleen Vernon, ed. The Spanish Civil War and the Visual Arts (Ithaca: Center for International Studies, Cornell University, 1990).

Curriculum Materials

Read and download ALBA’s lesson plan for Art and Propaganda in Republican Spain.