By: Anthony L. Geist, Peter N. Carroll

“It was amazing to see how many of these children could draw and draw well – and it was heartening to see how their talent was encouraged by the teachers.”

– Dorothy Parker (November 15, 1937)

Children’s Drawings of the Spanish Civil War

During the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) new tactics of warfare, including aerial bombardment, affected the civilian population as never before. As a result children were often displaced from their normal lives. It is estimated that as many as 200,000 child refugees fled the war zones. The Republican government provided assistance to most of them, but France also gave refuge to 25,000 Basque children; British private relief agencies took in 4,000, the Soviet Union 2,000, and Mexico 500. Spain responded to the crisis by placing children with foster families and by creating residential schools known as “Colonias Infantiles,” or Children’s Colonies in eastern Spain.

One such Colony was La Casa Ben Leider, named for an American aviator, journalist, and volunteer in the Lincoln Brigade, who was shot down and killed while flying for the Spanish Republic. In 1938 the children in this Colony created a remarkable booklet of drawings for Ben Leider’s family to commemorate his sacrifice.

One such Colony was La Casa Ben Leider, named for an American aviator, journalist, and volunteer in the Lincoln Brigade, who was shot down and killed while flying for the Spanish Republic. In 1938 the children in this Colony created a remarkable booklet of drawings for Ben Leider’s family to commemorate his sacrifice.

Teachers lived with the young refugees in the Colonies, assuring that their education continued despite conditions of war and displacement. One of the children’s projects was to draw pictures of their experiences of the war. Social workers and psychiatrists in the 1930s believed such artwork was an important tool to help children deal with the trauma of war and separation from their families. It is the first known systematic use of art as therapy for children in wartime. Six young American social workers went to Spain on a special delegation to evaluate the distribution of humanitarian aid. Among them were Jennie Berman Chakin, Thyra Edwards, Lillian Emder, Rosa Leff Gregg, Constance Kyle, and Virginia Malbin.

The children responded enthusiastically and produced thousands of drawings. According to a dispatch of the Spanish Information Bureau, 3000 of these drawings were first displayed in Valencia in an exhibition organized by the Spanish Ministry of Education. Subsequently 118 were selected for showing in England and the United States to raise funds for children’s relief efforts in Spain. The American Friends Service Committee and the Carnegie Institute in Madrid participated in the collection and exhibition of the children’s artwork. The exhibition was titled They Still Draw Pictures. The prominent author Aldous Huxley wrote an introduction to the exhibit catalog, which went through three printings in 1938-1939.

Many of the original drawings survive in various archives throughout the world. There are 609 at the Mandeville Special Collections Library of the University of California at San Diego; over 100 at Columbia University’s Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library; and still more at Harvard University, Haverford College, and the University of Washington. London’s Marx Memorial Library holds a number of drawings, as does the National Library in Madrid. There are online exhibits through the Archives of Ontario and the Biblioteca Nacional de España.

Images of Life Before the War

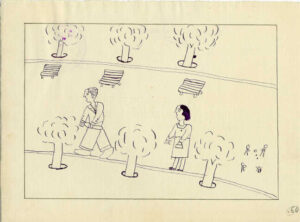

Among the most moving of the drawings are those that depict images of peace. The drawings in the first grouping –life before the war– vary considerably in topic and execution, but all have an orderly air about them, a sense of daily life as usual. They depict ordinary people –often featuring the artist as protagonist– doing ordinary things: a stroll in the park, returning from school, washing clothes, feeding the chickens. The children draw these scenes in loving detail. They evoke and idealize home, preserving on paper what they may never see again. Carmen Sierra, age 12, draws an urban park scene (at left). Well tended trees flank the path in two orderly rows. Carefully drafted park benches await passersby. A man and a woman walk from right to left. He holds what appears to be a loaf of bread in his left hand, she a purse. They are talking, perhaps arguing. In the lower right hand corner four tiny children play catch. Their rendering as stick figures without facial features stands in contrast to the adults, represented in realistic detail –cuffs and buttons, hair and faces, shoes and purse meticulously drawn. These are the stable features of the child’s world, they are what matter and merit attention.

Among the most moving of the drawings are those that depict images of peace. The drawings in the first grouping –life before the war– vary considerably in topic and execution, but all have an orderly air about them, a sense of daily life as usual. They depict ordinary people –often featuring the artist as protagonist– doing ordinary things: a stroll in the park, returning from school, washing clothes, feeding the chickens. The children draw these scenes in loving detail. They evoke and idealize home, preserving on paper what they may never see again. Carmen Sierra, age 12, draws an urban park scene (at left). Well tended trees flank the path in two orderly rows. Carefully drafted park benches await passersby. A man and a woman walk from right to left. He holds what appears to be a loaf of bread in his left hand, she a purse. They are talking, perhaps arguing. In the lower right hand corner four tiny children play catch. Their rendering as stick figures without facial features stands in contrast to the adults, represented in realistic detail –cuffs and buttons, hair and faces, shoes and purse meticulously drawn. These are the stable features of the child’s world, they are what matter and merit attention.

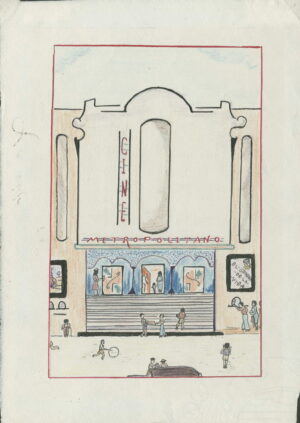

In his drawing of Madrid before the war, Guillermo Garcia Montano, 13 years old, shows people buying tickets to the monumental Cine Metropolitano movie house. Life proceeds as normal: a child holds its mother’s hand as they enter the theater; a passenger gets out of a taxi as a kid rolls a hoop down the sidewalk; a newsboy sells papers.

In his drawing of Madrid before the war, Guillermo Garcia Montano, 13 years old, shows people buying tickets to the monumental Cine Metropolitano movie house. Life proceeds as normal: a child holds its mother’s hand as they enter the theater; a passenger gets out of a taxi as a kid rolls a hoop down the sidewalk; a newsboy sells papers.

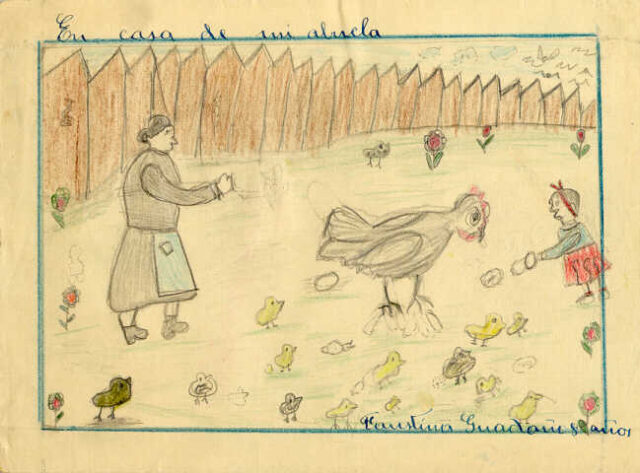

Faustina Guadano remembers her grandmother’s house from afar. She feeds a hen larger than herself as its chicks scurry around them. The disproportion, the error of realistic representation, reveals an emotional truth far greater than accuracy of scale could.

It is often difficult to determine whether these drawings represent life before or after the war. We can understand them simply as life without war. In either case, this is the world the child refugees only have access to in memory or imagination, images of peace fixed in color and shapes on paper.

It is often difficult to determine whether these drawings represent life before or after the war. We can understand them simply as life without war. In either case, this is the world the child refugees only have access to in memory or imagination, images of peace fixed in color and shapes on paper.

Children Depict the War

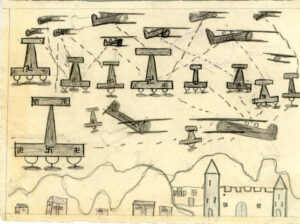

Among the most numerous and powerful drawings are those depicting war. They vary greatly in style and skill of execution; they depict cityscapes and country scenes, yet almost all of them have one thing in common: airplanes. Aerial combat and bombing were new, and the greatest terror came from the air. “They move like mechanized doom,” Robert Jordan remarks of the airplanes in Ernest Hemingway’s novel For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940). The children drew the planes in remarkably accurate detail.

Among the most numerous and powerful drawings are those depicting war. They vary greatly in style and skill of execution; they depict cityscapes and country scenes, yet almost all of them have one thing in common: airplanes. Aerial combat and bombing were new, and the greatest terror came from the air. “They move like mechanized doom,” Robert Jordan remarks of the airplanes in Ernest Hemingway’s novel For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940). The children drew the planes in remarkably accurate detail.

Many of the airplanes used by Franco’s forces to attack the civilian population were sent to Spain by Hitler’s Nazi Germany. These planes bore the insignia of the Nazi’s swastika on their wings. Rafael Barber, 10 years old, drew this picture of Nazi warplanes filling the sky. Their murderous geometry occupies nearly the entire drawing as the planes dwarf the town below. Their larger than life size, though unrealistic, rings true emotionally. The castle is useless to protect the village.

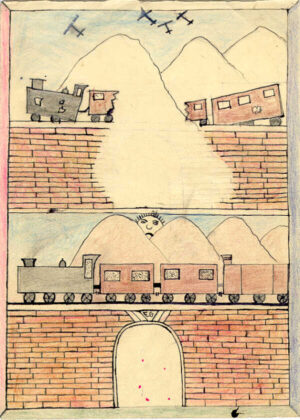

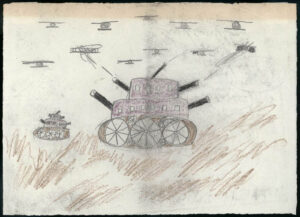

The drawing (at right) by ‘EG’ presents “before and after” scenes which should be read from bottom to top. The lower panel shows a train crossing a bridge; the sun peeks between two mountains. In the upper panel, the planes retreat after having destroyed the bridge and the train, upsetting the order and symmetry of “before.” Even one of the mountains has disappeared. The anonymous child artist seems to have intuited what Madison Avenue advertising agencies learned much later: that stories can be told with just the beginning and the end. Alberto Monos at age seven has caught the details of the engines of war in this drawing of combat (at left) between airplanes and tanks. Note how the larger tank has doubled itself, with guns coming out of both sides of the two turrets.

The drawing (at right) by ‘EG’ presents “before and after” scenes which should be read from bottom to top. The lower panel shows a train crossing a bridge; the sun peeks between two mountains. In the upper panel, the planes retreat after having destroyed the bridge and the train, upsetting the order and symmetry of “before.” Even one of the mountains has disappeared. The anonymous child artist seems to have intuited what Madison Avenue advertising agencies learned much later: that stories can be told with just the beginning and the end. Alberto Monos at age seven has caught the details of the engines of war in this drawing of combat (at left) between airplanes and tanks. Note how the larger tank has doubled itself, with guns coming out of both sides of the two turrets.

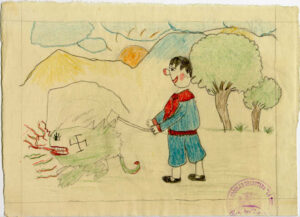

The artists of the Children’s Colonies depict war in many different ways, but one rarely finds expressions of pure fantasy among them. That makes this drawing, by the 12-year-old Margarita Arnao Crespo, so unique. In the background, trees, clouds and mountains, the sun peeking through them; in the foreground, a central figure. Yet this is not a scene witnessed or remembered. Rendered in cheerful colors it is a fanciful allegory of the triumph over fascism. A boy, a smile creasing his face, swings his ax at a fantastic fascist beast.

The artists of the Children’s Colonies depict war in many different ways, but one rarely finds expressions of pure fantasy among them. That makes this drawing, by the 12-year-old Margarita Arnao Crespo, so unique. In the background, trees, clouds and mountains, the sun peeking through them; in the foreground, a central figure. Yet this is not a scene witnessed or remembered. Rendered in cheerful colors it is a fanciful allegory of the triumph over fascism. A boy, a smile creasing his face, swings his ax at a fantastic fascist beast.

Leaving Home

The Spanish Civil War displaced upwards of 200,000 children who fled from violence and hunger. Spanish businessman Jose Weissberger, who worked closely with the New York-based Child Welfare Association, sent a cablegram in 1938 warning that: “Terrifying shortage cod liver oil [stop] Milk supply rapidly dwindling [stop] Sugar situation even worse [stop].”

In a number of drawings the children depicted the ordeal of their evacuation and flight. This visual evidence suggests how traumatic the experience was for them.

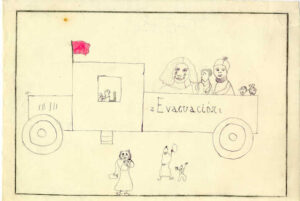

Margarita Garcia, aged ten, drew an image of her evacuation (at left). The central figure that immediately catches our eye is a weeping girl who we take to be Margarita. Enormous tears roll down her face as she looks directly at us. Her sorrow dwarfs everything else. The fact that she depicts herself much larger than all the other figures reveals an emotional truth. For the young artist there is only the sorrow of displacement. Other children depict their evacuation differently.

Margarita Garcia, aged ten, drew an image of her evacuation (at left). The central figure that immediately catches our eye is a weeping girl who we take to be Margarita. Enormous tears roll down her face as she looks directly at us. Her sorrow dwarfs everything else. The fact that she depicts herself much larger than all the other figures reveals an emotional truth. For the young artist there is only the sorrow of displacement. Other children depict their evacuation differently.

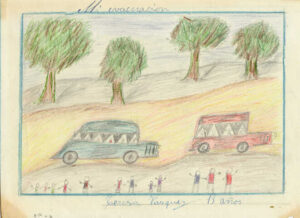

Teresa Vazquez, 13, shows no individual features in drawing her evacuation. All the people, both those leaving and those bidding them farewell from the roadside, are tiny stick figures. Hearse-like vehicles transport the evacuees, whom we glimpse between the gathered curtains, as though clutched in the black teeth of a monster.

Teresa Vazquez, 13, shows no individual features in drawing her evacuation. All the people, both those leaving and those bidding them farewell from the roadside, are tiny stick figures. Hearse-like vehicles transport the evacuees, whom we glimpse between the gathered curtains, as though clutched in the black teeth of a monster.

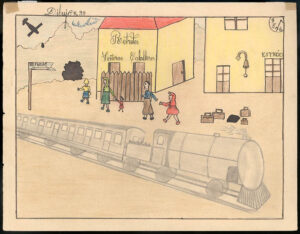

Mercedes Comellas Ricart, age 13, depicts the interruption of her family’s evacuation by an air raid. Notice the futuristic train that waits to whisk them to safety. Its sleek, streamlined contours stand in contrast to the black, jagged mouth of the shelter in the hill behind the station.

Mercedes Comellas Ricart, age 13, depicts the interruption of her family’s evacuation by an air raid. Notice the futuristic train that waits to whisk them to safety. Its sleek, streamlined contours stand in contrast to the black, jagged mouth of the shelter in the hill behind the station.

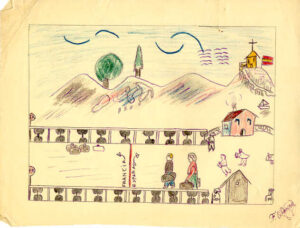

Yet another scene shows a family fleeing Iran into France. Fernando Olavera, age 13, has sketched the bridge, the border and the refugee couple in great detail. The church in the upper right-hand corner received special attention. The neatly lettered legend on the hill explains why: “San Marcial taken by the fascists.” The refugees take flight because the fascists have occupied San Marcial.

Yet another scene shows a family fleeing Iran into France. Fernando Olavera, age 13, has sketched the bridge, the border and the refugee couple in great detail. The church in the upper right-hand corner received special attention. The neatly lettered legend on the hill explains why: “San Marcial taken by the fascists.” The refugees take flight because the fascists have occupied San Marcial.

Life in the Colonias Infantiles

Far from the war’s violence, the Spanish government established Children’s Colonies to provide comfort and security to thousands of children displaced by the conflict. Whenever possible the Republic took over country estates and mansions abandoned by fascist sympathizers, along the coast or in the mountains. The Colonies had resident teachers and medical personnel to attend to the educational, physical, emotional and psychological needs of the children. In 1938 American social workers visited the Colonies. Despite the government’s efforts there were never enough colonies to accommodate all the young refugees.

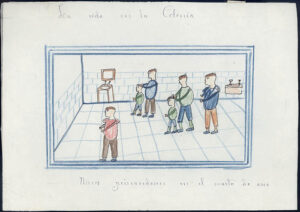

In 1937 the American writer Dorothy Parker wrote: “I have seen some of the Colonies. There is no dreadful orphan asylum quality about them. I never saw finer children — free and growing and happy.” Another American journalist, Martha Gellhorn wrote in a letter to Eleanor Roosevelt, the wife of US President Franklin D. Roosevelt: “They also draw pictures, because with some food in them (that’s all the food they have in them) they feel very lively and happy: so they make wonderful pictures of the Quakers-who distribute this food-in their home.” 11 year-old Ramon Luis draws boys combing their hair in the washroom at the Colonia Escolar de Estadilla (at left). Older boys help the younger ones get ready for the day’s activities.

In 1937 the American writer Dorothy Parker wrote: “I have seen some of the Colonies. There is no dreadful orphan asylum quality about them. I never saw finer children — free and growing and happy.” Another American journalist, Martha Gellhorn wrote in a letter to Eleanor Roosevelt, the wife of US President Franklin D. Roosevelt: “They also draw pictures, because with some food in them (that’s all the food they have in them) they feel very lively and happy: so they make wonderful pictures of the Quakers-who distribute this food-in their home.” 11 year-old Ramon Luis draws boys combing their hair in the washroom at the Colonia Escolar de Estadilla (at left). Older boys help the younger ones get ready for the day’s activities.

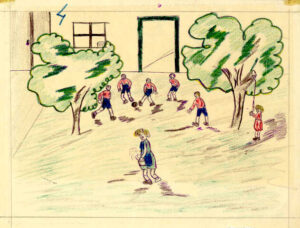

The drawing by Angeles Arnaiz, age 14, shows a detail of life in her Children’s Colony in southern France. She explains on the back of the picture that she has drawn herself ringing the lunch bell, as the cook carries a pot of stew across the courtyard. Five boys are playing soccer. Note the symmetry of the drawing, the open door to the Colony squarely centered in the back, two large trees holding the ballplayers in a protective embrace. The composition suggests order, play, nourishment and security.

The drawing by Angeles Arnaiz, age 14, shows a detail of life in her Children’s Colony in southern France. She explains on the back of the picture that she has drawn herself ringing the lunch bell, as the cook carries a pot of stew across the courtyard. Five boys are playing soccer. Note the symmetry of the drawing, the open door to the Colony squarely centered in the back, two large trees holding the ballplayers in a protective embrace. The composition suggests order, play, nourishment and security.

Children Draw Hope for the Future

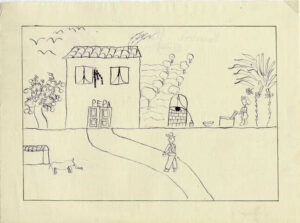

Born of the trauma of war many of these drawings reveal an understandable desire for a peaceful future. Carmen Sierra, age 12, drew an idyllic country scene. Smoke flows reassuringly from the chimney of a house, the name PEPA inscribed over the door. Birds, not bombers, fill the sky as trees recede in orderly rows behind the house. To the left a tree stands laden with fruit. To the right, a woman washes clothes under a palm tree. Whimsically, a dog quacks (“Cui”) at the mailman approaching with a letter in his hand. Everything is in its place.

Born of the trauma of war many of these drawings reveal an understandable desire for a peaceful future. Carmen Sierra, age 12, drew an idyllic country scene. Smoke flows reassuringly from the chimney of a house, the name PEPA inscribed over the door. Birds, not bombers, fill the sky as trees recede in orderly rows behind the house. To the left a tree stands laden with fruit. To the right, a woman washes clothes under a palm tree. Whimsically, a dog quacks (“Cui”) at the mailman approaching with a letter in his hand. Everything is in its place.

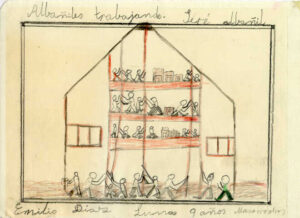

Nine year old Emilio Diaz Luna depicts masons at work. “I will be a mason,” he affirms in strong lettering. A large crew of workmen erect a house, working in concert. After so many buildings in flames or rubble, he will build or rebuild, constructing the future.

Nine year old Emilio Diaz Luna depicts masons at work. “I will be a mason,” he affirms in strong lettering. A large crew of workmen erect a house, working in concert. After so many buildings in flames or rubble, he will build or rebuild, constructing the future.

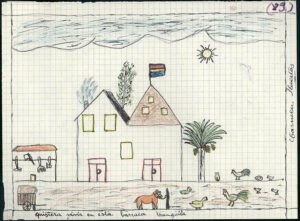

“I would like to live in this peaceful farmhouse,” 9 year-old Carmen Huertas writes on her picture (below). The sun shines over a house with smoke flowing from the chimney. The flag of the Spanish Republic flies from the highest peak of the roof as farm animals graze in the yard. All is in order, with no sign of war.

Despite these visions of peace Franco ruled Spain with an iron fist for the next 39 years. We have no way of knowing whether these children ever saw their dreams of the future fulfilled. Nevertheless, their drawings stand as testimony to the human spirit in the face of adversity.

Despite these visions of peace Franco ruled Spain with an iron fist for the next 39 years. We have no way of knowing whether these children ever saw their dreams of the future fulfilled. Nevertheless, their drawings stand as testimony to the human spirit in the face of adversity.

At least three children who survived the war have seen their drawings after more than sixty years.

Children’s Art from other Wars

The Spanish Civil War was the first conflict that inspired the creation of drawings by children who experienced the trauma of modern warfare. Tragically it was not the last. Children continue to be victims of war and violence. The following links will take you to collections of drawings done by young artists who depict their response to subsequent wars, from World War II to the present.

Kosovo Children’s Art:

http://webarchive.afsc.org/ewnews/kosart.htm

Uganda (1986-2005):

http://www.amnestyusa.org/child_soldiers/gallery.html