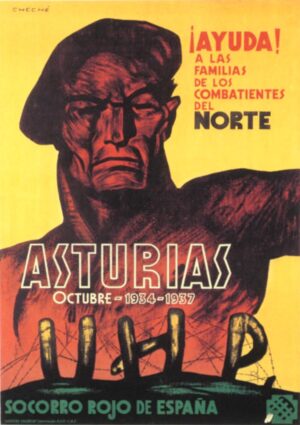

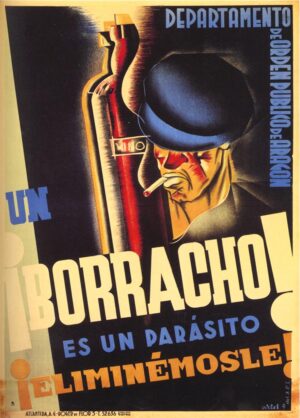

Throughout the war there were poster campaigns focused on particular needs and events. Thus when the Asturias were overrun by Franco’s troops posters like Cheche’s Aid the Families of the Fighters of the North (at left) helped focus public attention on the plight of the refugees. Continuing problems, like the perennial one of soldiers getting drunk on leave, would also be the focus of special publicity campaigns; hence Artel’s A Drunk! He is a parasite! Eliminate him! (right). Some issues and campaigns were the subject of posters throughout the war; the effort to promote literacy, one of the Republic’s key social agendas, was one of these. Other topics received more intermittent treatment; these include ecological posters warning people cutting wood for heat about the dangers of deforestation. The last year of the war, when the Republic was losing territory to the fascists, saw a number of posters aiming to help build morale, stiffen resistance, and reinforce solidarity. Slogans like “Resist,” “Counterattack,” or “Fortify” identify a poster as produced in 1938 rather than 1937.

Throughout the war there were poster campaigns focused on particular needs and events. Thus when the Asturias were overrun by Franco’s troops posters like Cheche’s Aid the Families of the Fighters of the North (at left) helped focus public attention on the plight of the refugees. Continuing problems, like the perennial one of soldiers getting drunk on leave, would also be the focus of special publicity campaigns; hence Artel’s A Drunk! He is a parasite! Eliminate him! (right). Some issues and campaigns were the subject of posters throughout the war; the effort to promote literacy, one of the Republic’s key social agendas, was one of these. Other topics received more intermittent treatment; these include ecological posters warning people cutting wood for heat about the dangers of deforestation. The last year of the war, when the Republic was losing territory to the fascists, saw a number of posters aiming to help build morale, stiffen resistance, and reinforce solidarity. Slogans like “Resist,” “Counterattack,” or “Fortify” identify a poster as produced in 1938 rather than 1937.

There were new posters continually throughout the war and in time old ones would disappear from stores and be covered over on the streets with new issues. One of the most useful things to know would be the exact week that each poster was published. Definite proof would not always be available, but a search through daily newspapers and weekly magazines from 1936-39 could produce a list of poster reproductions; that would set latest dates of appearance for a number of posters. Also helpful would be a detailed chronology of wartime slogans and cultural campaigns; that would give likely dates for many of the posters bearing such slogans. Though there are many detailed military and political chronologies of the war, we lack a comparably detailed cultural chronology. Again, no one has yet done this research in Spanish publications, but it could be done. All this would enable far more precise readings of the posters than scholars have produced to date.

There were new posters continually throughout the war and in time old ones would disappear from stores and be covered over on the streets with new issues. One of the most useful things to know would be the exact week that each poster was published. Definite proof would not always be available, but a search through daily newspapers and weekly magazines from 1936-39 could produce a list of poster reproductions; that would set latest dates of appearance for a number of posters. Also helpful would be a detailed chronology of wartime slogans and cultural campaigns; that would give likely dates for many of the posters bearing such slogans. Though there are many detailed military and political chronologies of the war, we lack a comparably detailed cultural chronology. Again, no one has yet done this research in Spanish publications, but it could be done. All this would enable far more precise readings of the posters than scholars have produced to date.

Even without being able to date and contextualize each poster, we can, however, give some overall feeling for the rich, mutually reinforcing semiotic environment in which many of the posters were displayed. Those that were published and displayed for particular week-long campaigns, for example, would have seemed not isolated objects to be noticed or ignored but rather part of city-wide activities and celebrations concentrated on a single topic. Thus a week-long campaign to build support for the Republic’s new regular army was held throughout loyalist Spain in February 1937. Numerous posters were created for the occasion and displayed all along the streets. In Barcelona’s Plaza de Catalunya a huge soldier designed by sculptor Miguel Paredes was constructed of wood, wire, and plaster of Paris. At the week’s end a parade was held; as the army marched through Barcelona’s Paseo de Gracia and Plaza de Catalunya, literally tens of thousands of volunteers held posters and placards aloft. Meanwhile numerous pamphlets and postcards were printed to supplement the posters, along with smaller decorations that people could attach to their clothing.

Even without being able to date and contextualize each poster, we can, however, give some overall feeling for the rich, mutually reinforcing semiotic environment in which many of the posters were displayed. Those that were published and displayed for particular week-long campaigns, for example, would have seemed not isolated objects to be noticed or ignored but rather part of city-wide activities and celebrations concentrated on a single topic. Thus a week-long campaign to build support for the Republic’s new regular army was held throughout loyalist Spain in February 1937. Numerous posters were created for the occasion and displayed all along the streets. In Barcelona’s Plaza de Catalunya a huge soldier designed by sculptor Miguel Paredes was constructed of wood, wire, and plaster of Paris. At the week’s end a parade was held; as the army marched through Barcelona’s Paseo de Gracia and Plaza de Catalunya, literally tens of thousands of volunteers held posters and placards aloft. Meanwhile numerous pamphlets and postcards were printed to supplement the posters, along with smaller decorations that people could attach to their clothing.

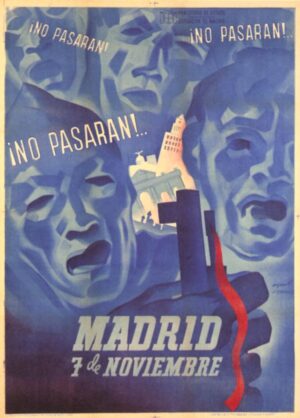

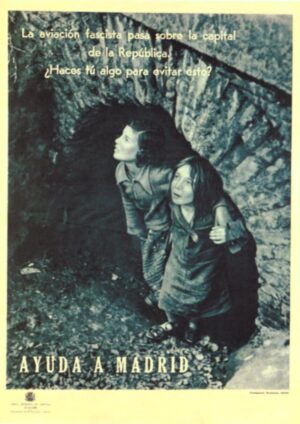

Large multifaceted cultural events focused on other week-long campaigns as well. A week of support for the Basque region, held from May 29 to June 6, 1937, brought out posters, banners, and placards with Basque motifs. A monument symbolizing the sacred tree of Guernica was erected in the Plaza de Catalunya, and the Basque play Pedro Mari was performed in the Liceo theater on Barcelona’s Ramblas; poster artists designed the sets. The opening performance was interrupted by a bombing raid, but the cast and audience spurned the air raid shelters and stayed on singing the “Internationale.” Later that summer a week advocating Aid to Madrid (at left) followed. That fall special celebrations to honor the International Brigades were held in Madrid. On September 5 a mass meeting adorned with posters and banners produced for the occasion was held in the Monumental Cinema. Posters advertising the meeting and other posters honoring the I.B. went up across the city. Pamphlets were issued about the event, as was a book of poems about the volunteer soldiers.

Large multifaceted cultural events focused on other week-long campaigns as well. A week of support for the Basque region, held from May 29 to June 6, 1937, brought out posters, banners, and placards with Basque motifs. A monument symbolizing the sacred tree of Guernica was erected in the Plaza de Catalunya, and the Basque play Pedro Mari was performed in the Liceo theater on Barcelona’s Ramblas; poster artists designed the sets. The opening performance was interrupted by a bombing raid, but the cast and audience spurned the air raid shelters and stayed on singing the “Internationale.” Later that summer a week advocating Aid to Madrid (at left) followed. That fall special celebrations to honor the International Brigades were held in Madrid. On September 5 a mass meeting adorned with posters and banners produced for the occasion was held in the Monumental Cinema. Posters advertising the meeting and other posters honoring the I.B. went up across the city. Pamphlets were issued about the event, as was a book of poems about the volunteer soldiers.