Picture yourself one moonlit night in Madrid late in 1936. Visibility is good, so the fascist bombers are out in force. Germany’s Adolph Hitler has provided his Condor Legion to help General Francisco Franco bomb his own capital city into submission. As the residents of Barcelona would also come to learn in the course of the war, five hundred pound bombs are a serious weapon; they burrow deep into a building before exploding. Meanwhile, at the city’s edge, high on Mount Garabitas above the wooded hills of the Casa de Campo, Franco’s soldiers have set the sights of their artillery pieces on the city’s landmarks. The Telephonica building gives them a range finder and a line of sight.

Picture yourself one moonlit night in Madrid late in 1936. Visibility is good, so the fascist bombers are out in force. Germany’s Adolph Hitler has provided his Condor Legion to help General Francisco Franco bomb his own capital city into submission. As the residents of Barcelona would also come to learn in the course of the war, five hundred pound bombs are a serious weapon; they burrow deep into a building before exploding. Meanwhile, at the city’s edge, high on Mount Garabitas above the wooded hills of the Casa de Campo, Franco’s soldiers have set the sights of their artillery pieces on the city’s landmarks. The Telephonica building gives them a range finder and a line of sight.

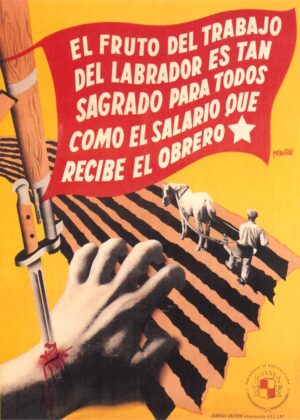

When the air raid siren sounds you seek out the nearby subway refugio. There, as people gather together amidst repeated detonations, powerless, unable to strike back, the bright colors of the posters on the subway walls remind you that elsewhere your comrades are striking back. And they remind you that the city’s anguish is at once exemplary and exceptional, that it is the object of the world’s attention. Later, when the sun rises over smoking ruins, it brightens the bold colors of resistance and solidarity on posters covering walls still standing. Madrid is of one mind; these posters are its hues and its icons, the forms in which it knows itself.