Inevitably, visitors and volunteers began sending the posters home; there was no more economical way to communicate the passion of the war. Here, on a single sheet typically thirty inches wide and forty high, was a powerful synecdoche for the war’s anguish and its idealism – a woman holding a murdered child, the working classes looking up as they yearned for liberation, the archetypal soldier now taking a stand against the evil of fascism. Inevitably too, not only in Spain but across Europe and in America as well, exhibitions were mounted to give people a chance to see numbers of posters at once. Few at the time doubted that art and politics were here decisively fused, for the posters were both aesthetically beautiful or terrifying and politically compelling. They cried out to be seen and acted upon; between the two impulses no space of doubt need fall. If we have unlearned this lesson in the intervening years, now seems an appropriate occasion to have it displayed for a different generation.

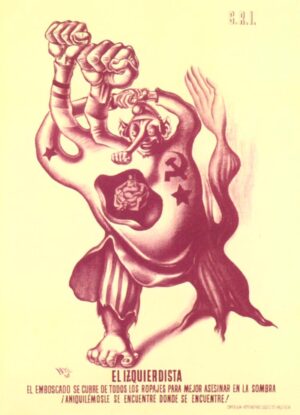

When American volunteers wrote home about the posters they saw and sometimes sent back to friends and family, it was, often as not, an individual poster that would engage their attention. Leon Rosenthal, writing home in August 1937, took some relish in comparing a friend back home to one of Ramon Puyol’s satiric portraits, The Ultraleftist / El Izquierdista (at left): “As for Gershon – I wish I had the poster I would like to send him – it shows the super-leftist – with two arms on the right shoulder raised in 2 fists and one left one – and a fist for a nose…and inside his belly is a fat bourgeois sitting on a soft chair & smoking a cigar.”

When American volunteers wrote home about the posters they saw and sometimes sent back to friends and family, it was, often as not, an individual poster that would engage their attention. Leon Rosenthal, writing home in August 1937, took some relish in comparing a friend back home to one of Ramon Puyol’s satiric portraits, The Ultraleftist / El Izquierdista (at left): “As for Gershon – I wish I had the poster I would like to send him – it shows the super-leftist – with two arms on the right shoulder raised in 2 fists and one left one – and a fist for a nose…and inside his belly is a fat bourgeois sitting on a soft chair & smoking a cigar.”

Dave Gordon, writing in July 1938, concentrated on a poster with little dramatic color but with a decisive cultural message:

Who hasn’t seen thousands of posters, whether for advertising or for propaganda? (Of course the advertising is only another type of propaganda itself.) Has there ever been a poster which did not contain a rather more than less obvious moral tailing along, either in the watchwords or catchwords or in the photograph, or drawing? It would be hard to find one which spoke for itself. It is extremely difficult to present the lesson desired without some concise wording or without plainly indicating the idea graphically.

Yet this is exactly what was done in a poster issued by the Generalitat of Catalonia. What is more, this particular poster deals with the principal pride of Catalonia, with what so strongly characterizes its special individuality and comprehends all of its cultural traits — the Catalan language.

Picture to yourself a photo-montage of two pages of a newspaper, one more and the other less obliquely reproduced on a huge poster sheet. Remember, too, that these newspaper pages are taken from a rebel fascist newspaper, impertinently bearing the name Unidad. The name “Catalonia” is printed in large letters, once at the head and once at the foot of the poster. Part of one of the newspapers is underscored in black. The underscored lines are only one sentence in a longer article. The paper is written in the Castilian tongue. The specially marked portion, translated, reads: “Jose Juan Jubert (fined) 100 pesetas and Javier Gibert Porrero, 100 pesetas, for speaking in Catalan at the table in the dining room of a hotel.” The newspaper, published in San Sebastian, bears the date January 6, 1938. The news item is a report of the court procedure of a day at the fascist tribunals.

The poster carries no more than what I have explained above. Yet it speaks worlds. It reflects a profound confidence in the understanding and pride of the Catalan. At the same time it reveals a grand contempt for the dogs of fascism who aim to crush the culture of the regions of Spain. It is a convincing call to all Catalonia to fight with Spain to defeat fascism if it wishes to retain its freedoms.

It is a simple poster, colored simply. I wish I had a copy to send you so that I need not have been compelled to describe it in words. It speaks most eloquently for itself. Yet I can’t help writing about it for two reasons — it impressed me considerably and I could not get a copy of it.