At this point the outcome of the rising was by no means certain. The Republicans held most of the navy, air-force and territory, including the capital and the vital industrial regions of the Basque Country and Catalonia. The rebels controlled the majority of the army, though the northern army, under General Mola, was paralyzed by a lack of arms and ammunition, and unexpected resistance from workers’ militias, and the formidable Army of Africa, under the command of General Franco, was trapped in Morocco.

However, forces outside Spain decisively altered the progress of the conflict. Initially, following Jose Giral’s desperate plea for assistance, Léon Blum, the French Prime Minister, had wished to aid the Republic and had authorized the sending of military aid, such as a number of aircraft arranged by Andre Malraux, a French pilot who organized a squadron of French pilots to fight for the Republic. However, following pressure from the British Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, and aware of the dangers of civil war in his own country should his government support the Spanish republic, Blum proposed an international agreement not to intervene in the conflict and a ‘non-intervention’ committee was established in London to oversee the agreement. However, as the agreement was ignored from the outset by Germany and Italy and, later, by Russia, while other neutral countries such as Britain and the United States took no action against firms providing supplies to the Rebels, the agreement was singularly ineffective.

Meanwhile, despite initial reluctance to support what they saw as a risky enterprise (and despite their official adherence to the non-intervention agreement) both Hitler and Mussolini responded to requests from Franco for assistance by sending twelve Italian Savoia-Marchetti S.81 and thirty German JU 52s bombers, which allowed Franco to airlift the Army of Africa across the Gibraltar strait. The Army of Africa then advanced swiftly northwards towards Madrid and by August 10 they had reached Merida where they linked up Franco’s southern zone with the northern zone of General Mola. The rebels then turned on the town of Badajoz, the capital of Extremadura. Despite a desperate defense, the town was captured and a brutal repression followed, during which nearly 2,000 people were shot. Stories and rumors of this savagery preceded the advance of the rebel army on Madrid, and worked considerably to the rebels’ advantage. Militiamen, terrified at the prospect of being outflanked, retreated headlong, often dropping their weapons and ammunition, back along the main roads to Madrid, where they could be picked off with ease by the advancing rebel forces.

Meanwhile, despite initial reluctance to support what they saw as a risky enterprise (and despite their official adherence to the non-intervention agreement) both Hitler and Mussolini responded to requests from Franco for assistance by sending twelve Italian Savoia-Marchetti S.81 and thirty German JU 52s bombers, which allowed Franco to airlift the Army of Africa across the Gibraltar strait. The Army of Africa then advanced swiftly northwards towards Madrid and by August 10 they had reached Merida where they linked up Franco’s southern zone with the northern zone of General Mola. The rebels then turned on the town of Badajoz, the capital of Extremadura. Despite a desperate defense, the town was captured and a brutal repression followed, during which nearly 2,000 people were shot. Stories and rumors of this savagery preceded the advance of the rebel army on Madrid, and worked considerably to the rebels’ advantage. Militiamen, terrified at the prospect of being outflanked, retreated headlong, often dropping their weapons and ammunition, back along the main roads to Madrid, where they could be picked off with ease by the advancing rebel forces.

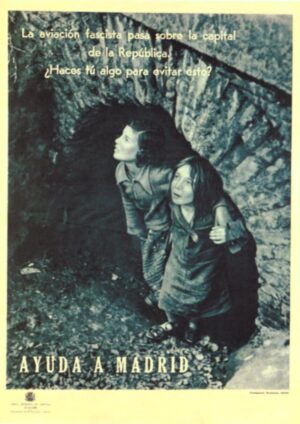

At the end of September, the rebel army made another detour to lift the siege of the city of Toledo which, crucially, allowed the defending Republicans time to prepare the defenses in Madrid. After another massacre of militiamen, the march towards Madrid resumed. By November 1, the rebels had reached the south-west of Madrid adjacent to the Casa de Campo and University City. Here, at last, the advance was slowed by a defense established by militia units and the desperate population of Madrid. On November 10, 1936, the last ditch defense was joined by an international column of volunteers; the first of the International Brigades, determined to help ensure that Madrid would not fall, that the rebel army would not pass.