JAN. 7. Barcelona beautiful. Streets aflame with posters of all parties for all causes, some of them put out by combinations of parties.

So wrote American volunteer Robert Merriman in his diary when he arrived in Spain at the beginning of 1937. Spain’s foreign minister Alvarez del Vayo was still more eloquent in his 1940 memoir. Full-color posters, banners, and fliers, brandishing dramatic swaths of red and black or blue or yellow were all over the city: along the streets, taped to windows, tacked up on kiosks in every public square, on the interior walls of office buildings and private homes, in all the subway stations, on the sides of buses, trucks, and even trains. By the second week of the war, early in July 1936, they were already defining the public space of major cities. Daily Worker correspondent George Marion, writing to Time magazine on his return home — his March 1, 1938, letter is unpublished but a copy is in his file at the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives — reported that “the posters flow from a hundred sources. During the many months I was in Spain I found the collection of posters just about a full-time job because there was no central source.” Many, he continued, were “put out by non-governmental bodies: trade unions, youth organizations, women’s committee, Fifth Regiment, and others.” On the Puerto del Sol, central square of Madrid, one hugh poster on the side of a building occupied a whole floor. Soon they appeared on bulletin boards and at headquarters at the fronts where men were fighting. They gave people information they needed, built morale, and focused debate and action on the key issues and campaigns of a given week. Communication, exhortation, persuasion, instruction, celebration, warning: all these aims and more were served by the 1,500 to 2,000 different posters appearing in the Spanish Republic from 1936-38. Of this number, perhaps 20 percent were exclusively textual; the rest of the posters were preeminently pictorial.

They were first of all an excellent mode of communication for a population with a high rate of illiteracy. For many years, Spain’s Catholic church, in control of public education, believed there was no need for either peasants or women to read. The Republic would begin rapidly to reverse that pattern, but in the meantime posters in public places combining striking iconography with brief slogans made it possible to get basic messages out to people quickly. The combination of strong graphics with concise captions also made the posters memorable and convincing.

They were first of all an excellent mode of communication for a population with a high rate of illiteracy. For many years, Spain’s Catholic church, in control of public education, believed there was no need for either peasants or women to read. The Republic would begin rapidly to reverse that pattern, but in the meantime posters in public places combining striking iconography with brief slogans made it possible to get basic messages out to people quickly. The combination of strong graphics with concise captions also made the posters memorable and convincing.

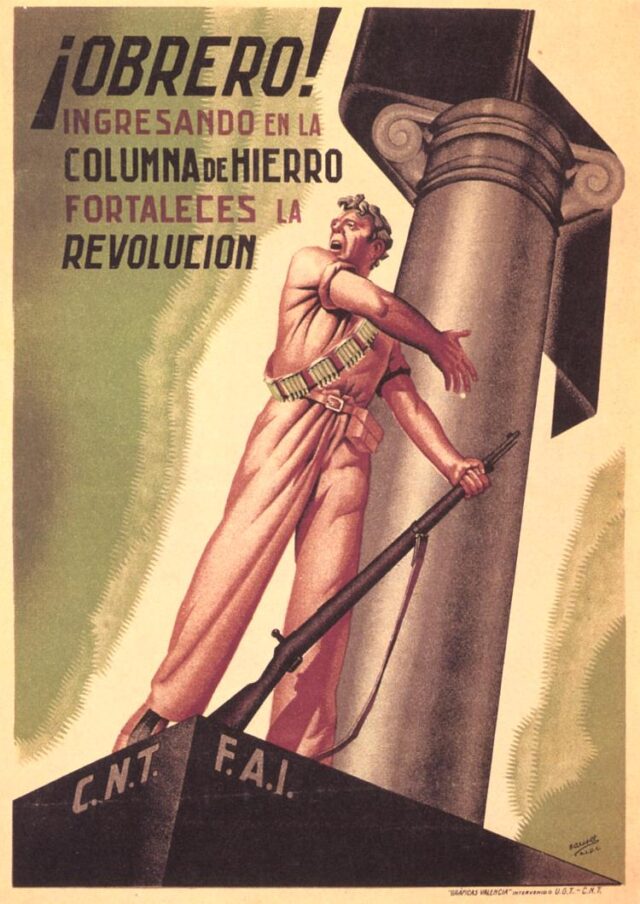

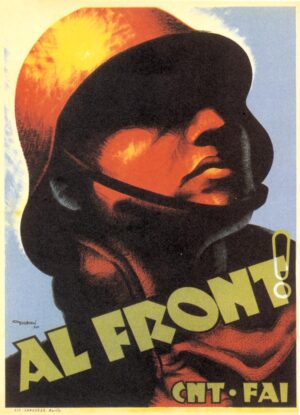

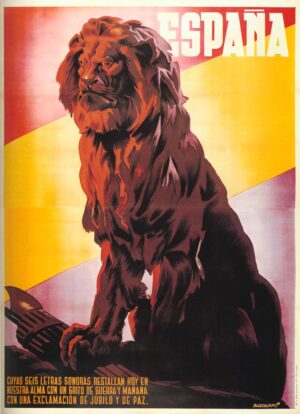

Early on large numbers of them were essentially recruitment posters. Carles Fontsere’s Al Front urged everyone to turn their eyes and their full attention to the rapidly expanding war; its helmeted soldier negotiated all the extremes of light and dark in such a way as to suggest there was no world outside the imperiled horizon of battle. In the presence of this icon there might seem no alternative but to volunteer. So too with Jose Bardasano’s España. All available and politically relevant nobility is combined in its lion’s confident stance and gaze of warm concern; stand with honor, the poster urges us, and give yourself over to be gathered into the country’s protective vigilance. These highly general inducements to solidarity and commitment were balanced with special pleas for particular militias. “Workers!” declared one of J. Bauset’s posters, “joining the Iron Column fortifies the revolution.” The iron column was an anarchist battalion, but other militias had their recruitment posters as well. In such cases, moreover, the posters went beyond literal recruitment. They amounted to ideological recruitment, urging people to place their faith and their loyalty with a particular political point of view. About some poster artists little is known, but basic biographical informations does exist for several, including Bardasano, Fontsere, Francisca, Puyol, Renau, and Sim — who are unquestionably among the most important poster artists of the war.

Early on large numbers of them were essentially recruitment posters. Carles Fontsere’s Al Front urged everyone to turn their eyes and their full attention to the rapidly expanding war; its helmeted soldier negotiated all the extremes of light and dark in such a way as to suggest there was no world outside the imperiled horizon of battle. In the presence of this icon there might seem no alternative but to volunteer. So too with Jose Bardasano’s España. All available and politically relevant nobility is combined in its lion’s confident stance and gaze of warm concern; stand with honor, the poster urges us, and give yourself over to be gathered into the country’s protective vigilance. These highly general inducements to solidarity and commitment were balanced with special pleas for particular militias. “Workers!” declared one of J. Bauset’s posters, “joining the Iron Column fortifies the revolution.” The iron column was an anarchist battalion, but other militias had their recruitment posters as well. In such cases, moreover, the posters went beyond literal recruitment. They amounted to ideological recruitment, urging people to place their faith and their loyalty with a particular political point of view. About some poster artists little is known, but basic biographical informations does exist for several, including Bardasano, Fontsere, Francisca, Puyol, Renau, and Sim — who are unquestionably among the most important poster artists of the war.