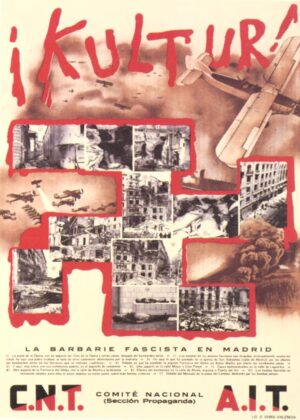

In response to the desperate situation facing the Republic a true Popular Front government was formed in September 1936 containing, in addition to Republican parties, members of the PCE and PSOE. One month later, despite their ideological opposition, four representatives of the anarcho-syndicalist CNT also joined the cabinet.

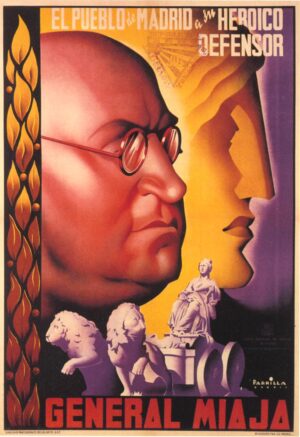

By mid-October, the artillery fire of the approaching Army of Africa could be heard in Madrid and by early November elements of the Nationalist Army had reached the south-western suburbs. The Republican government was so convinced that Madrid would fall that, on 6 November, it left for Valencia, and placed the protection of the city in the hands of a military Junta de Defensa, under General Miaja.

By mid-October, the artillery fire of the approaching Army of Africa could be heard in Madrid and by early November elements of the Nationalist Army had reached the south-western suburbs. The Republican government was so convinced that Madrid would fall that, on 6 November, it left for Valencia, and placed the protection of the city in the hands of a military Junta de Defensa, under General Miaja.

However, helped by vital Russian military aid, the newly arrived 11th International Brigade and the Communist Party’s Fifth Regiment, the population of Madrid embarked on a desperate defence, spurred on by the defiant speeches of Dolores Ibarruri, La Pasionaria. There was desperate hand-to-hand fighting as Moroccan troops almost reached the city centre, but the defenders drove them back. By the end of November, the Nationalist attack was spent and the city, for the moment, held out.

The following month, in December, the rebels began an attempt to cut the Madrid-La Coruna road to the north-west of the capital. After heavy losses in fighting around the village of Boadilla del Monte, the attack was called off before, on January 5, the assault was renewed. During four days of fighting, for very little strategic gain by the rebels, each side lost in the region of 15,000 men. Casualties among the International Brigades were particularly high.

In February 1937 the rebels made a renewed attempt to surround Madrid by cutting the road to Valencia in the Jarama valley to the south of the Spanish capital. Republican troops reinforced by International Brigades, including British and Americans, were thrown in to the defence. Again the forces of the Republican Army held on desperately, allowing the rebels to make little progress and again the number of casualties was enormous. The Republicans lost perhaps 25,000 and the Nationalists 20,000.

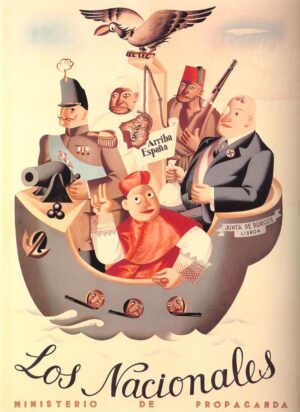

On March 1, Franco agreed to a new two-pronged offensive to the east of the capital pressed upon him by Mussolini, flushed with the recent capture of Malaga by Italian forces. The plan involved an attack by Italian troops at Guadalajara, supported by Spanish forces moving on Alcala de Henares from Jarama. However, the Italians became bogged down by determined Republican resistance, aided by appalling weather conditions that prevented the rebel air-force from operating effectively. On March 12, the Republican forces, including Italian members of the International Brigades, launched a counter-attack. When the Nationalist offensive at Jarama failed to materialise, the Republicans routed the Italian forces. Mussolini responded furiously by declaring that Italian forces would remain in Spain until a Nationalist victory washed away the shame of their defeat at Guadalajara.

On March 1, Franco agreed to a new two-pronged offensive to the east of the capital pressed upon him by Mussolini, flushed with the recent capture of Malaga by Italian forces. The plan involved an attack by Italian troops at Guadalajara, supported by Spanish forces moving on Alcala de Henares from Jarama. However, the Italians became bogged down by determined Republican resistance, aided by appalling weather conditions that prevented the rebel air-force from operating effectively. On March 12, the Republican forces, including Italian members of the International Brigades, launched a counter-attack. When the Nationalist offensive at Jarama failed to materialise, the Republicans routed the Italian forces. Mussolini responded furiously by declaring that Italian forces would remain in Spain until a Nationalist victory washed away the shame of their defeat at Guadalajara.

With Nationalist efforts to capture Madrid essentially defeated, the war moved to the north of Spain as Franco attempted to overcome Basque forces who, despite their Catholic beliefs, had remained loyal to a Republic which offered a level of autonomy fervently opposed by the rebels. As the Nationalist forces gradually closed on the heavily fortified city of Bilbao, the rebels launched an air attack on the ancient Basque market town of Guernica. In one afternoon of bombing, the undefended wooden town was razed to the ground by the German Condor legion. Attempts by the Nationalists to deny responsibility for the atrocity were quickly and effectively shown to be false and the bombing of Guernica took on a central significance in the war, immortalised by the famous painting by Picasso.

In May 1937 cracks in the Republican Popular Front coalition became significantly wider, when what was essentially a civil war erupted in Barcelona. Despite the inclusion of four anarchists into the Republican government, contradictions between Republicans, moderate Socialists and Communists on one hand and the revolutionary proletarian groups on the other had remained a burning issue for the Republic. The immediate catalyst of the May events was the raid on the CNT-controlled central telephone exchange ordered on May 3 by the PSUC police commissioner for Catalonia. The CNT and the POUM fought on for several days until the CNT leadership, only too aware that the civil war could only help Franco, instructed its militants to lay down their arms. Under strong pressure from the Communists, the Republic then set about ensuring the complete destruction of the POUM. In the ensuing crackdown the POUM leader, Andres Nin, was arrested and later murdered by the NKVD. Others members, including George Orwell, prudently went into hiding. The POUM was banned in June 1937, and moves were made to suppress the collectives and re-impose centralised government. By 1938 little of the autonomy granted by the Popular Front would remain

In May 1937 cracks in the Republican Popular Front coalition became significantly wider, when what was essentially a civil war erupted in Barcelona. Despite the inclusion of four anarchists into the Republican government, contradictions between Republicans, moderate Socialists and Communists on one hand and the revolutionary proletarian groups on the other had remained a burning issue for the Republic. The immediate catalyst of the May events was the raid on the CNT-controlled central telephone exchange ordered on May 3 by the PSUC police commissioner for Catalonia. The CNT and the POUM fought on for several days until the CNT leadership, only too aware that the civil war could only help Franco, instructed its militants to lay down their arms. Under strong pressure from the Communists, the Republic then set about ensuring the complete destruction of the POUM. In the ensuing crackdown the POUM leader, Andres Nin, was arrested and later murdered by the NKVD. Others members, including George Orwell, prudently went into hiding. The POUM was banned in June 1937, and moves were made to suppress the collectives and re-impose centralised government. By 1938 little of the autonomy granted by the Popular Front would remain

The following month, in June 1937, Bilbao fell to the advancing Nationalist forces. The Republic responded by launching a major offensive at Brunete on July 6, designed to relieve pressure on the northern front and break through the rebels at their weakest point to the west of Madrid. However, despite initial Republican gains, Franco was able to bring his superior numbers to bear and gradually pushed back the republican forces.

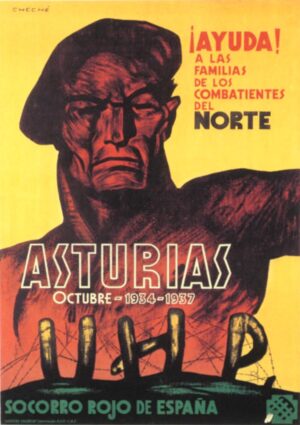

With the failure of the Brunete offensive, Franco was able to continue with his northern offensive, and Santander fell to the rebels at the end of August. Again the Republicans tried to divert attention from the northern front by launching an offensive in Aragon aimed at capturing Saragossa. Though inroads into Aragon were made- International Brigades were heavily involved in capturing Quinto and Belchite despite heavy casualties- Saragossa remained in rebel hands, and the rest of the Basque regions and Asturias fell to the rebels by October 1937. The loss of the northern ports and the vital heavy industries was a crucial blow to the Republic.

With the failure of the Brunete offensive, Franco was able to continue with his northern offensive, and Santander fell to the rebels at the end of August. Again the Republicans tried to divert attention from the northern front by launching an offensive in Aragon aimed at capturing Saragossa. Though inroads into Aragon were made- International Brigades were heavily involved in capturing Quinto and Belchite despite heavy casualties- Saragossa remained in rebel hands, and the rest of the Basque regions and Asturias fell to the rebels by October 1937. The loss of the northern ports and the vital heavy industries was a crucial blow to the Republic.

Despite these losses the Republic launched a surprise attack in December 1937 and captured Teruel. In freezing winter conditions the Republic’s best troops, including the International Brigades and the Communist 5th Regiment, fought desperately, but outnumbered, they were unable to prevent Franco bringing his superior numbers of arms and men to bear. The Nationalists recaptured Teruel in February 1938.

The following month, on March 7, 1938, Franco launched a massive and well-prepared attack in Aragon involving 100,000 men, 200 tanks and over 600 Italian and German planes. What began as a series of break-throughs for the Nationalists swiftly became outright retreat for the exhausted Republican forces, as their lines virtually collapsed under the ferocious and well-supplied offensive. By April 15, the rebels had reached the Mediterranean and cut the Republic in two, and by the end of the month the rebels held a fifty-mile stretch of coast. Had Franco headed north into Catalonia he would probably have ended the war a year earlier than he did. However, Franco’s aim was not to defeat the Republic, but to annihilate it forever.

The following month, on March 7, 1938, Franco launched a massive and well-prepared attack in Aragon involving 100,000 men, 200 tanks and over 600 Italian and German planes. What began as a series of break-throughs for the Nationalists swiftly became outright retreat for the exhausted Republican forces, as their lines virtually collapsed under the ferocious and well-supplied offensive. By April 15, the rebels had reached the Mediterranean and cut the Republic in two, and by the end of the month the rebels held a fifty-mile stretch of coast. Had Franco headed north into Catalonia he would probably have ended the war a year earlier than he did. However, Franco’s aim was not to defeat the Republic, but to annihilate it forever.

Three months later, in July 1938, the Republic launched what would become their last act when Republican forces advanced back across the River Ebro. A special Army of the Ebro was formed for the offensive, which was placed under the command of the Communist General Juan Modesto. But, as had happened too many times for the Republic, initial successes soon ground to a halt when faced with the nationalists’ hugely superior numbers and armaments. The battle of the Ebro lasted for over three months until, bled to death, the Republican Army collapsed.

Meanwhile, events outside Spain had effectively sealed the Republic’s fate when Czechoslovakia had been essentially “surrendered” to the Nazis at the Munich Agreement of September 29, 1938. Spanish premier Negrín’s hopes of assistance from the western democracies were dashed but, nevertheless, Juan Negrín withdrew the International Brigades in October, gambling that pressure would be put on Franco to respond in kind, by sending back German and Italian troops. But it was too late. Supplied with fresh armaments from Germany, Franco’s offensive of November 1938 sounded the death knell for the Republic and, by January, Franco had captured Barcelona.

Meanwhile, events outside Spain had effectively sealed the Republic’s fate when Czechoslovakia had been essentially “surrendered” to the Nazis at the Munich Agreement of September 29, 1938. Spanish premier Negrín’s hopes of assistance from the western democracies were dashed but, nevertheless, Juan Negrín withdrew the International Brigades in October, gambling that pressure would be put on Franco to respond in kind, by sending back German and Italian troops. But it was too late. Supplied with fresh armaments from Germany, Franco’s offensive of November 1938 sounded the death knell for the Republic and, by January, Franco had captured Barcelona.

On March 4, Colonel Casado, commander of the Republican Army of the Centre, launched a revolt in Madrid in an attempt to bring the war to an end. The revolt against the Republican government sparked off the second civil war in the Republican zone as Casado’s forces battled with Communists who were determined to fight on. Over 200 were killed before Casado’s forces gained control and an attempt was made to negotiate peace with Franco. However, Franco refused to negotiate and instead, on March 26, launched a gigantic and virtually unopposed Nationalist advance along a wide front. The following day Nationalists entered Madrid and, by March 31, 1939, all of Spain was in Nationalist hands. On April 1, 1939 Franco announced that the Spanish Civil War was officially at an end.