4 R

The Spanish Civil War accelerated a radical transformation in the status of women in the Republic. Women took up work in the factories; they had wide access to education for the first time; their legal status was secured; women’s organizations and cultural journals were founded; abortion was legalized; and, most surprisingly from the viewpoint of the rest of the world, women fought in the front lines in the opening months of the war.

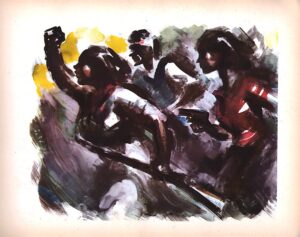

The first months of the war also saw a series of gendered posters. Spanish women were urged to join the militias, to take up arms with men and boys. Even now, these images, including Sim’s remarkable portraits of armed women in battle, have the power to surprise us. Sim’s images of armed women striding forward purposefully in battle are still striking and unconventional, even after sixty years. But the series of prints actually plays havoc with gender stereotypes in a variety of ways. The captions to Battering Ram and Rest are gender neutral, and the prints depict men and women as equals. The captions to She Saw Him Fall (at left) and She Knew How to Die substitute female pronouns in rhetoric more familiar from paeans to male heroism and resolve and thus demolish the notion that these traits are gender specific. The captions to Youth and They Shall Not Pass, on the other hand, are partly inflected to account for their gendered subject. Most conventional of all, of course, is Delirium, which shows a  nurse ministering to a feverish soldier. But there are several prints in the series devoted to the medical services, and one, In the Thick of the Fight, shows a militiaman and a nurse carrying a wounded figure from a battle in progress; the gender neutral caption describes them both as “symbols of the revolution . . . muscles taut and a spark of rebelliousness in their hearts.” Of the thirty-one prints in the series (plus one on the cover), all executed in 1936 and not all depicting people, fifteen of them have women as their sole or equal subject. Sim’s Estampas de la Revolucion Espanola 19 Julio de 1936 was published in Barcelona by the propaganda offices of the CNT/FAI.

nurse ministering to a feverish soldier. But there are several prints in the series devoted to the medical services, and one, In the Thick of the Fight, shows a militiaman and a nurse carrying a wounded figure from a battle in progress; the gender neutral caption describes them both as “symbols of the revolution . . . muscles taut and a spark of rebelliousness in their hearts.” Of the thirty-one prints in the series (plus one on the cover), all executed in 1936 and not all depicting people, fifteen of them have women as their sole or equal subject. Sim’s Estampas de la Revolucion Espanola 19 Julio de 1936 was published in Barcelona by the propaganda offices of the CNT/FAI.

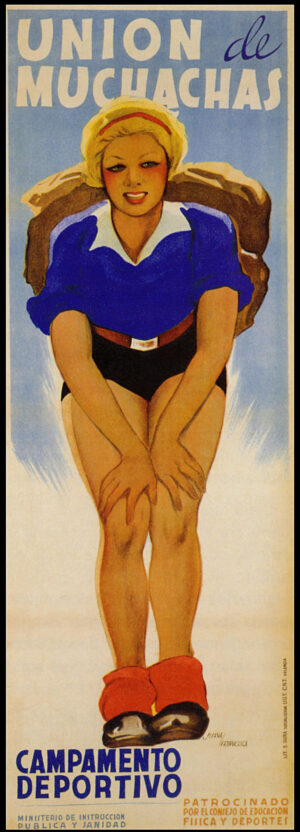

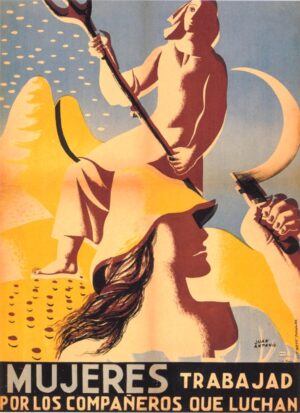

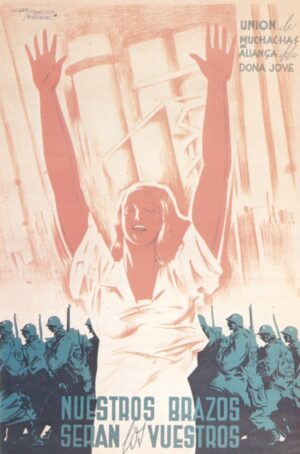

By spring 1937, however, it became clear to many that the militias would not suffice to fight large-scale battles in a prolonged war; a centrally organized army was required to meet coordinated attacks by columns of infantry, tanks, and planes. Meanwhile, the army needed to increase its size as well, thereby leaving behind fewer men to keep Spain’s industries running. Women were not sent back to the home, their traditional site in Spain, but they disappeared from combat as the militias were dissolved; instead, posters appearing from mid-1937 on urged them to take up the slack in industry and agriculture. Juan Antonio’s Women, Work for the Comrades Who Fight (at right) is a good example of that sort of poster, as is a poster jointly designed by Juana Francisca and Jose Bardasano, Our Arms wll be Yours (below).

By spring 1937, however, it became clear to many that the militias would not suffice to fight large-scale battles in a prolonged war; a centrally organized army was required to meet coordinated attacks by columns of infantry, tanks, and planes. Meanwhile, the army needed to increase its size as well, thereby leaving behind fewer men to keep Spain’s industries running. Women were not sent back to the home, their traditional site in Spain, but they disappeared from combat as the militias were dissolved; instead, posters appearing from mid-1937 on urged them to take up the slack in industry and agriculture. Juan Antonio’s Women, Work for the Comrades Who Fight (at right) is a good example of that sort of poster, as is a poster jointly designed by Juana Francisca and Jose Bardasano, Our Arms wll be Yours (below).

One of the most telling pieces of visual evidence of the disappearance of women from combat is Sim’s second portfolio of drawings, 12 Escenas de Guerra. In his first collection of battle illustrations, Estampas de la Revolucion Espanola 19 Julio de 1936, women are portrayed in about half of the illustrations; 12 Escenas de Guerra is devoted entirely to men. His first portfolio, notably, was published by the anarchists. The second collection was issued by the central government, the Generalitat, of Catalonia. The second collection also uses less vibrant color, emphasizing the brown uniforms of the regular army rather than the red and black colors of anarchism.

One of the most telling pieces of visual evidence of the disappearance of women from combat is Sim’s second portfolio of drawings, 12 Escenas de Guerra. In his first collection of battle illustrations, Estampas de la Revolucion Espanola 19 Julio de 1936, women are portrayed in about half of the illustrations; 12 Escenas de Guerra is devoted entirely to men. His first portfolio, notably, was published by the anarchists. The second collection was issued by the central government, the Generalitat, of Catalonia. The second collection also uses less vibrant color, emphasizing the brown uniforms of the regular army rather than the red and black colors of anarchism.