Biography

Susman, William. (Ellis, William Robert; Sussman, Samuel; Dorno; William); b. September 15 (25), 1915 New Haven (Bethel), Connecticut; Jewish; High School education 3 years did not graduate; 1 year New York National Guard, 258th Field Artillery; Single; Seaman and Party Organizer; CP 1929 (1935) and YCL, NMU; Arrived in Spain on December 23, 1937; Served with the XV Brigade, Estado Mayor, SIM; Rank Teniente; Returned to the US on December 20, 1938 aboard the Ausonia; WWII US Army, ETO, rank Sergeant, after the end of the war he was sent to the Philippines; d. February 21, 2003, Sarasota, Florida; Before leaving for Spain Susman recruited volunteers for the IB in Puerto Rico; Susman was one of the founders of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives.

Sources: Cadre (under William Robert Ellis); RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 885, ll. 81-90, photo under Ellis, William Robert and autobiographical sketch; ALBA 107 William Sussman Papers; ALBA AUDIO 107 William Sussman Audio Collection; ALBA VIDEO 107 Bill Susman Videos; (obituary) The Volunteer, Volume 25, No. 2, June 2003, pp. 3, 18- 20; L-W Tree Ancestry.

Biography: There really were only two options—getting wounded or getting killed. This a young lieutenant in the Lincoln Battalion realized as he started up a steep hill in the Ebro valley near Gandesa. The Americans and their Spanish comrades were caught in a crossfire between two machine gun emplacements above them. The idea that you could pass through that ricocheting rain of bullets unscathed was not worth entertaining. But the Republic needed the high ground. The effort had to be made whether or not it was realistic. As Bill Susman would learn over and over again in Spain, occupying the high ground morally did not guarantee possession of the equivalent geographical or political terrain. Like so many of his lifetime comrades on the Left, he would learn the lesson repeatedly in the years to come. But he did indeed live to scale other mountains. On that day in 1938 he was wounded in the elbow and crawled behind a terrace to avoid being shot again. Carried out of action, he would live to win and lose many future battles, bearing with him at once the knowledge that you are never wholly in control of your own fate and that the only compensatory leverage you have is never to exercise less than a maximum effort. Those of us who worked with Bill over the years would come to feel a certain awe at what a maximum effort meant for him. When you were in the crossfire between his will and his affection you were not likely to forget the experience. He began life as a red diaper baby, born Samuel Susman to Charles and Anna Susman in New Haven, Connecticut, on September 25, 1915. They returned to their home in Bridgeport, Connecticut, where Bill spent his first years. The household was a transit point for radicals passing through the area. Both parents worked in clothing factories. Anna was active in the ILGWU, as was Bill’s great aunt Sarah, who lived for some time in the household. Charles was a Socialist Party member when his son was born, and he became a charter member of the new Communist Party. The marriage collapsed when Bill was about six years old; in 1929 Bill and his father moved to the Bronx. Bill was an honors student in high school, but nonetheless felt restless. Susman entered the party’s junior Groups of America at age ten, then became a Young Pioneer. They sent him to Chicago to attend the first national Unemployment Councils convention; immediately after that he graduated into the Young Communist League. By that time, in a Bronx high school, he was simultaneously taking courses at the Party’s Worker School. He was eager for adventure, for travel, and Left politics had become central to his life. He undertook some special work under the name William Dorno. The new first name stuck, and he became William Susman. He dropped out of school and in 1934 was assigned to help the striking Maritime Workers Industrial Union. When the strike ended, he decided to go to sea. On the New York docks he showed a skill he would employ successfully the rest of his life - choosing just the right words to tip an interaction his way. From on board ship they called out to the men below looking for work to say they needed a chef’s assistant. Never skipping a beat then or thereafter, Bill proclaimed himself well seasoned. “Where have you worked?” “The Hotel Edison, the Roosevelt, the Waldorf.” It was the third claim, the topper, that got him in trouble a few days out to sea, when the captain called down for a Waldorf salad. Bill hadn’t a clue. In recompense they kept him at the job without quarter. He never quite got out of his clothes, but when the captain came down for a visit a few days later he took a liking to the ship’s young scullery scoundrel and invited him on deck to learn something about being a sailor. He had a steering lesson and adapted obliquely to another task. Directed by a seaman with a heavy Brooklyn accent to call out “The lights are bright, sir,” when eight bells rang, thereby assuring all that the running lights were on, Bill heard the command through his Yiddish ears and for a time bellowed “Litza Britza.” After passing through the Panama Canal and disembarking on shore leave at San Francisco, he was ready to become involved in a West Coast strike by way of the waterfront YCL. Back in New York in 1936, he went to sea again, joining the east coast strike when the ship docked in Baltimore. By then, a young CP member, he was ready for a still more specific role. He jumped ship in Puerto Rico to become a Party organizer. There he learned Spanish, organized a Puerto Rican students union, and helped form a union on a pine plantation in the center of the island. Then history intervened in the form of a civil war in Spain. His Spanish was about to become still more useful. He began to recruit Puerto Ricans for the International Brigades. Assigned to help set up arrangements in Paris for Latin American volunteers, he returned to New York and sailed for Europe in service of Spain in 1937. This time he traveled as William Robert Ellis. On board with him were a score of his Puerto Rican volunteers. After a little over three months in Paris, Susman was delayed yet a bit longer in his effort to cross the border into Spain. He was asked to make a small purchase first. A German civilian aircraft had landed in Paris and was up for sale. Bill was given $50,000 in cash, along with an ancient and utterly unreliable revolver for self-protection, and sent off to the airport to close the deal. The plane would be especially useful in Spain, since its German markings reduced the chance it would be fired upon by fascist troops. Then, at last, Bill did cross the Spanish border. Thereafter he remembered more vividly the time in trenches, the time with comrades. All that flooded over him forty years later, after Franco had died, when he finally returned to Spain. As he wrote in the Volunteer, he sat silently on a bench in the Plaza de Cataluna in Barcelona in 1977 and “wept without knowing why.” There would be many reasons to weep over the years. Among them would be the stupidity of the American military when he enlisted in the army shortly after Pearl Harbor. Repeatedly refused promotion and denied formal officer training, he found himself an instructor in hand-to-hand combat, setting mines, and defusing booby traps, skills he had acquired in an earlier life. Every officer who recommended Bill for promotion would himself be transferred out. When he finally got a chance to see his file he found it marked “Promotion Denied—fought with Reds in Spain.” Meanwhile, anticipating a week’s furlough from Fort Bragg, he wrote to his girlfriend (and native New Yorker) Helene Shemel: “Take your Wassermann test. I’m coming up.” That was his proposal; they were married on April 17, 1942. Then he did get to the European theater, where other ironies abounded: Bill discovered the only way he could question German prisoners was to use his Yiddish. When the war in Europe ended, Sergeant Susman was shipped off to the Philippines. His outfit was assigned to block any effort by the Philippine liberation fighters, who had long fought the Japanese, to take their rightful place in national politics. His fellow soldiers had their eyes opened after they broke the rules and fraternized with the Huk. Conversations about equality, democracy, and freedom ensued, conversations Bill had once engaged in under the dappled shade of olive trees. The Huk would subsequently mount a Communist-led peasant rebellion (1946-54), but were defeated with the help of U.S supplied arms. Bill was back home early in 1946; the following year his daughter Susan was born. Meanwhile, an army buddy had called to ask what he knew about broilers. “What’s to know?” Bill replied, “a chicken’s a chicken.” But the friend had a different broiler in mind than the countertop appliance. Signed on to manage a Manhattan factory assembling kitchen broilers, he did so until a return stint to Puerto Rico. There were tax incentives to manufacturing on the island, so Bill found himself commuting to manage a women’s glove factory. The enterprise floundered after the boss was caught embezzling from the firm. Then Bill began representing other mainland manufacturers. Plexiglas. B.V.D.s. He hated selling, disliked the traveling, and found work under capitalism inherently contradictory as a progressive. But he had a family to support, a family that moved to Fresh Meadows, Queens in 1951 and finally to Great Neck in 1959. In Queens Bill was elected a Democratic Assemblyman. His son Paul was born in 1950. Then the shadow of McCarthyism fell over the land. Like so many Spanish vets, Susman found employment still more fragile. The FBI kept calling employers, and every time he was out of a job. Ironically, the FBI assault occurred just as Susman had drifted away from the Party. The final psychological break would come with the Khrushchev revelations of 1956, but Bill was already disengaged before then. For one thing neither his recent nor his future employment left much time for work in mass organizations. The job scene changed dramatically when a break came in the mid-1950s. There was an opening at MPO, a New York film production house with nine stages and an office in L.A. They were doing industrial and educational shorts. When television took off, they became one of the country’s largest producers of commercials. Marvin Rothenberg, a progressive member of the MPO Board, had helped get Bill a job. It was, as they say, an opening at the bottom. Bill started by delivering coffee and carrying cans of film. But he studied to become an assistant director, passed an exam, moved up to stage manager, and ended as Executive Vice President. Suddenly capitalism and Left politics coalesced, at least in Bill’s own practice. He successfully hired Black workers when other firms would not, and he and Marvin helped them form their own union. Confronted with that fait accompli, the main union was then compelled to accept Black members. Bill also built relationships with political filmmakers from Algeria, Argentina, and Mexico. He was able to get them film, and he was able to get their film developed. He assisted distributors of political films. In 1979 Susman took on one last great project, the creation of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives. - From The Volunteer, Vol. 25, no. 2, by Cary Nelson.

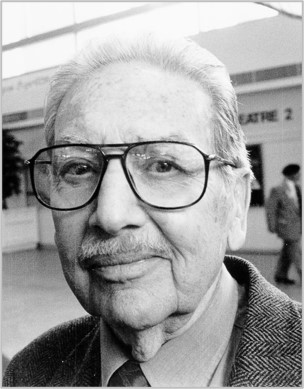

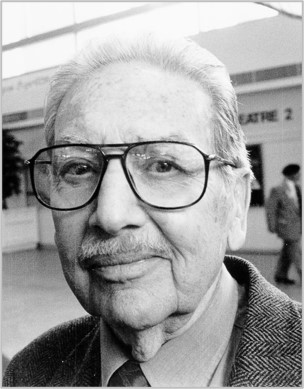

Photographs: William Susman, May 1938. The 15th International Brigade Photographic Unit Photograph Collection; ALBA Photo 11; ALBA Photo number 11-0024. Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives. Elmer Holmes Bobst Library, 70 Washington Square South, New York, NY 10012, New York University Libraries; RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 885, 997.; Bill Susman, by Richard Bermack.

Sources: Cadre (under William Robert Ellis); RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 885, ll. 81-90, photo under Ellis, William Robert and autobiographical sketch; ALBA 107 William Sussman Papers; ALBA AUDIO 107 William Sussman Audio Collection; ALBA VIDEO 107 Bill Susman Videos; (obituary) The Volunteer, Volume 25, No. 2, June 2003, pp. 3, 18- 20; L-W Tree Ancestry.

Biography: There really were only two options—getting wounded or getting killed. This a young lieutenant in the Lincoln Battalion realized as he started up a steep hill in the Ebro valley near Gandesa. The Americans and their Spanish comrades were caught in a crossfire between two machine gun emplacements above them. The idea that you could pass through that ricocheting rain of bullets unscathed was not worth entertaining. But the Republic needed the high ground. The effort had to be made whether or not it was realistic. As Bill Susman would learn over and over again in Spain, occupying the high ground morally did not guarantee possession of the equivalent geographical or political terrain. Like so many of his lifetime comrades on the Left, he would learn the lesson repeatedly in the years to come. But he did indeed live to scale other mountains. On that day in 1938 he was wounded in the elbow and crawled behind a terrace to avoid being shot again. Carried out of action, he would live to win and lose many future battles, bearing with him at once the knowledge that you are never wholly in control of your own fate and that the only compensatory leverage you have is never to exercise less than a maximum effort. Those of us who worked with Bill over the years would come to feel a certain awe at what a maximum effort meant for him. When you were in the crossfire between his will and his affection you were not likely to forget the experience. He began life as a red diaper baby, born Samuel Susman to Charles and Anna Susman in New Haven, Connecticut, on September 25, 1915. They returned to their home in Bridgeport, Connecticut, where Bill spent his first years. The household was a transit point for radicals passing through the area. Both parents worked in clothing factories. Anna was active in the ILGWU, as was Bill’s great aunt Sarah, who lived for some time in the household. Charles was a Socialist Party member when his son was born, and he became a charter member of the new Communist Party. The marriage collapsed when Bill was about six years old; in 1929 Bill and his father moved to the Bronx. Bill was an honors student in high school, but nonetheless felt restless. Susman entered the party’s junior Groups of America at age ten, then became a Young Pioneer. They sent him to Chicago to attend the first national Unemployment Councils convention; immediately after that he graduated into the Young Communist League. By that time, in a Bronx high school, he was simultaneously taking courses at the Party’s Worker School. He was eager for adventure, for travel, and Left politics had become central to his life. He undertook some special work under the name William Dorno. The new first name stuck, and he became William Susman. He dropped out of school and in 1934 was assigned to help the striking Maritime Workers Industrial Union. When the strike ended, he decided to go to sea. On the New York docks he showed a skill he would employ successfully the rest of his life - choosing just the right words to tip an interaction his way. From on board ship they called out to the men below looking for work to say they needed a chef’s assistant. Never skipping a beat then or thereafter, Bill proclaimed himself well seasoned. “Where have you worked?” “The Hotel Edison, the Roosevelt, the Waldorf.” It was the third claim, the topper, that got him in trouble a few days out to sea, when the captain called down for a Waldorf salad. Bill hadn’t a clue. In recompense they kept him at the job without quarter. He never quite got out of his clothes, but when the captain came down for a visit a few days later he took a liking to the ship’s young scullery scoundrel and invited him on deck to learn something about being a sailor. He had a steering lesson and adapted obliquely to another task. Directed by a seaman with a heavy Brooklyn accent to call out “The lights are bright, sir,” when eight bells rang, thereby assuring all that the running lights were on, Bill heard the command through his Yiddish ears and for a time bellowed “Litza Britza.” After passing through the Panama Canal and disembarking on shore leave at San Francisco, he was ready to become involved in a West Coast strike by way of the waterfront YCL. Back in New York in 1936, he went to sea again, joining the east coast strike when the ship docked in Baltimore. By then, a young CP member, he was ready for a still more specific role. He jumped ship in Puerto Rico to become a Party organizer. There he learned Spanish, organized a Puerto Rican students union, and helped form a union on a pine plantation in the center of the island. Then history intervened in the form of a civil war in Spain. His Spanish was about to become still more useful. He began to recruit Puerto Ricans for the International Brigades. Assigned to help set up arrangements in Paris for Latin American volunteers, he returned to New York and sailed for Europe in service of Spain in 1937. This time he traveled as William Robert Ellis. On board with him were a score of his Puerto Rican volunteers. After a little over three months in Paris, Susman was delayed yet a bit longer in his effort to cross the border into Spain. He was asked to make a small purchase first. A German civilian aircraft had landed in Paris and was up for sale. Bill was given $50,000 in cash, along with an ancient and utterly unreliable revolver for self-protection, and sent off to the airport to close the deal. The plane would be especially useful in Spain, since its German markings reduced the chance it would be fired upon by fascist troops. Then, at last, Bill did cross the Spanish border. Thereafter he remembered more vividly the time in trenches, the time with comrades. All that flooded over him forty years later, after Franco had died, when he finally returned to Spain. As he wrote in the Volunteer, he sat silently on a bench in the Plaza de Cataluna in Barcelona in 1977 and “wept without knowing why.” There would be many reasons to weep over the years. Among them would be the stupidity of the American military when he enlisted in the army shortly after Pearl Harbor. Repeatedly refused promotion and denied formal officer training, he found himself an instructor in hand-to-hand combat, setting mines, and defusing booby traps, skills he had acquired in an earlier life. Every officer who recommended Bill for promotion would himself be transferred out. When he finally got a chance to see his file he found it marked “Promotion Denied—fought with Reds in Spain.” Meanwhile, anticipating a week’s furlough from Fort Bragg, he wrote to his girlfriend (and native New Yorker) Helene Shemel: “Take your Wassermann test. I’m coming up.” That was his proposal; they were married on April 17, 1942. Then he did get to the European theater, where other ironies abounded: Bill discovered the only way he could question German prisoners was to use his Yiddish. When the war in Europe ended, Sergeant Susman was shipped off to the Philippines. His outfit was assigned to block any effort by the Philippine liberation fighters, who had long fought the Japanese, to take their rightful place in national politics. His fellow soldiers had their eyes opened after they broke the rules and fraternized with the Huk. Conversations about equality, democracy, and freedom ensued, conversations Bill had once engaged in under the dappled shade of olive trees. The Huk would subsequently mount a Communist-led peasant rebellion (1946-54), but were defeated with the help of U.S supplied arms. Bill was back home early in 1946; the following year his daughter Susan was born. Meanwhile, an army buddy had called to ask what he knew about broilers. “What’s to know?” Bill replied, “a chicken’s a chicken.” But the friend had a different broiler in mind than the countertop appliance. Signed on to manage a Manhattan factory assembling kitchen broilers, he did so until a return stint to Puerto Rico. There were tax incentives to manufacturing on the island, so Bill found himself commuting to manage a women’s glove factory. The enterprise floundered after the boss was caught embezzling from the firm. Then Bill began representing other mainland manufacturers. Plexiglas. B.V.D.s. He hated selling, disliked the traveling, and found work under capitalism inherently contradictory as a progressive. But he had a family to support, a family that moved to Fresh Meadows, Queens in 1951 and finally to Great Neck in 1959. In Queens Bill was elected a Democratic Assemblyman. His son Paul was born in 1950. Then the shadow of McCarthyism fell over the land. Like so many Spanish vets, Susman found employment still more fragile. The FBI kept calling employers, and every time he was out of a job. Ironically, the FBI assault occurred just as Susman had drifted away from the Party. The final psychological break would come with the Khrushchev revelations of 1956, but Bill was already disengaged before then. For one thing neither his recent nor his future employment left much time for work in mass organizations. The job scene changed dramatically when a break came in the mid-1950s. There was an opening at MPO, a New York film production house with nine stages and an office in L.A. They were doing industrial and educational shorts. When television took off, they became one of the country’s largest producers of commercials. Marvin Rothenberg, a progressive member of the MPO Board, had helped get Bill a job. It was, as they say, an opening at the bottom. Bill started by delivering coffee and carrying cans of film. But he studied to become an assistant director, passed an exam, moved up to stage manager, and ended as Executive Vice President. Suddenly capitalism and Left politics coalesced, at least in Bill’s own practice. He successfully hired Black workers when other firms would not, and he and Marvin helped them form their own union. Confronted with that fait accompli, the main union was then compelled to accept Black members. Bill also built relationships with political filmmakers from Algeria, Argentina, and Mexico. He was able to get them film, and he was able to get their film developed. He assisted distributors of political films. In 1979 Susman took on one last great project, the creation of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives. - From The Volunteer, Vol. 25, no. 2, by Cary Nelson.

Photographs: William Susman, May 1938. The 15th International Brigade Photographic Unit Photograph Collection; ALBA Photo 11; ALBA Photo number 11-0024. Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives. Elmer Holmes Bobst Library, 70 Washington Square South, New York, NY 10012, New York University Libraries; RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 885, 997.; Bill Susman, by Richard Bermack.