During the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) new tactics of warfare, including aerial bombardment, affected the civilian population as never before. As a result, children were often displaced from their normal lives. It is estimated that as many as 200,000 child refugees fled the war zones. The Republican government provided assistance to most of them, but France also gave refuge to 25,000 Basque children; British private relief agencies took in 4,000, the Soviet Union 2,000, and Mexico 500. Spain responded to the crisis by placing children with foster families and by creating residential schools known as “Colonias Infantiles,” or Children’s Colonies in eastern Spain.

During the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) new tactics of warfare, including aerial bombardment, affected the civilian population as never before. As a result, children were often displaced from their normal lives. It is estimated that as many as 200,000 child refugees fled the war zones. The Republican government provided assistance to most of them, but France also gave refuge to 25,000 Basque children; British private relief agencies took in 4,000, the Soviet Union 2,000, and Mexico 500. Spain responded to the crisis by placing children with foster families and by creating residential schools known as “Colonias Infantiles,” or Children’s Colonies in eastern Spain.

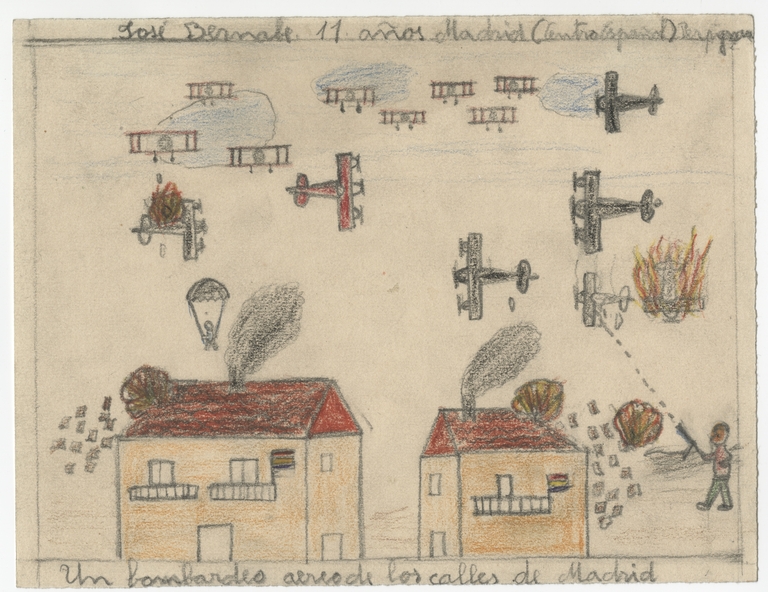

Teachers lived with the young refugees in the Colonies, assuring that their education continued despite conditions of war and displacement. One of the children’s projects was to draw pictures of their experiences of the war. Social workers and psychiatrists in the 1930s believed such artwork was an important tool to help children deal with the trauma of war and separation from their families. It is the first known systematic use of art as therapy for children in wartime. Six young American social workers went to Spain on a special delegation to evaluate the distribution of humanitarian aid. Among them were Jennie Berman Chakin, Thyra Edwards, Lillian Emder, Rosa Leff Gregg, Constance Kyle, and Virginia Malbin.

The children responded enthusiastically and produced thousands of drawings. According to a dispatch of the Spanish Information Bureau, 3000 of these drawings were first displayed in Valencia in an exhibition organized by the Spanish Ministry of Education. Subsequently, 118 were selected for showing in England and the United States to raise funds for children’s relief efforts in Spain. The American Friends Service Committee and the Carnegie Institute in Madrid participated in the collection and exhibition of the children’s artwork. The exhibition was titled They Still Draw Pictures. The prominent author Aldous Huxley wrote an introduction to the exhibit catalog, which went through three printings in 1938-1939. (See here for a copy of the catalog at The Internet Archive.)

Many of the original drawings survive in various archives throughout the world. There are 1,171 at the Biblioteca Nacional de España (Spain’s National Library); 609 at the Mandeville Special Collections Library of the University of California at San Diego (very usefully displayed here); over 100 at Columbia University’s Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library; and still more at Harvard University, Haverford College, and the University of Washington. London’s Marx Memorial Library holds a number of drawings, as does the National Library in Madrid. There are online exhibits through the Archives of Ontario and the Biblioteca Nacional de España.

For more information, including lesson plan suggestions: