Far from the war’s violence, the Spanish government established Children’s Colonies to provide comfort and security to thousands of children displaced by the conflict. Whenever possible the Republic took over country estates and mansions abandoned by fascist sympathizers, along the coast or in the mountains. The Colonies had resident teachers and medical personnel to attend to the educational, physical, emotional and psychological needs of the children. In 1938 American social workers visited the Colonies. Despite the government’s efforts there were never enough colonies to accommodate all the young refugees.

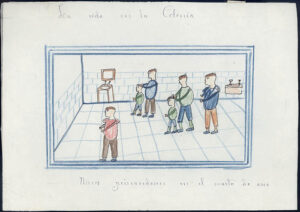

In 1937 the American writer Dorothy Parker wrote: “I have seen some of the Colonies. There is no dreadful orphan asylum quality about them. I never saw finer children — free and growing and happy.” Another American journalist, Martha Gellhorn wrote in a letter to Eleanor Roosevelt, the wife of US President Franklin D. Roosevelt: “They also draw pictures, because with some food in them (that’s all the food they have in them) they feel very lively and happy: so they make wonderful pictures of the Quakers-who distribute this food-in their home.” 11 year-old Ramon Luis draws boys combing their hair in the washroom at the Colonia Escolar de Estadilla (at left). Older boys help the younger ones get ready for the day’s activities.

In 1937 the American writer Dorothy Parker wrote: “I have seen some of the Colonies. There is no dreadful orphan asylum quality about them. I never saw finer children — free and growing and happy.” Another American journalist, Martha Gellhorn wrote in a letter to Eleanor Roosevelt, the wife of US President Franklin D. Roosevelt: “They also draw pictures, because with some food in them (that’s all the food they have in them) they feel very lively and happy: so they make wonderful pictures of the Quakers-who distribute this food-in their home.” 11 year-old Ramon Luis draws boys combing their hair in the washroom at the Colonia Escolar de Estadilla (at left). Older boys help the younger ones get ready for the day’s activities.

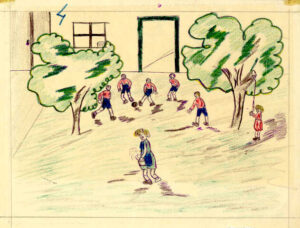

The drawing by Angeles Arnaiz, age 14, shows a detail of life in her Children’s Colony in southern France. She explains on the back of the picture that she has drawn herself ringing the lunch bell, as the cook carries a pot of stew across the courtyard. Five boys are playing soccer. Note the symmetry of the drawing, the open door to the Colony squarely centered in the back, two large trees holding the ballplayers in a protective embrace. The composition suggests order, play, nourishment and security.

The drawing by Angeles Arnaiz, age 14, shows a detail of life in her Children’s Colony in southern France. She explains on the back of the picture that she has drawn herself ringing the lunch bell, as the cook carries a pot of stew across the courtyard. Five boys are playing soccer. Note the symmetry of the drawing, the open door to the Colony squarely centered in the back, two large trees holding the ballplayers in a protective embrace. The composition suggests order, play, nourishment and security.