About ‘Robeson in Spain’

Paul Robeson’s concerns about fascism in the 1930s—military aggression, racial injustice, civilian bombings, and forced population displacement—remain issues of our own times. Seven decades later, ALBA’s magazine, The Volunteer, published a comic titled Robeson in Spain, detailing Robeson’s activism and dedication to the Spanish cause. It is ALBA’s hope that this work of art, history, and research can be embraced and appreciated by students of history and by the public as a way to convey the progressive ideals of Paul Robeson and the volunteers of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade.

Paul Robeson’s concerns about fascism in the 1930s—military aggression, racial injustice, civilian bombings, and forced population displacement—remain issues of our own times. Seven decades later, ALBA’s magazine, The Volunteer, published a comic titled Robeson in Spain, detailing Robeson’s activism and dedication to the Spanish cause. It is ALBA’s hope that this work of art, history, and research can be embraced and appreciated by students of history and by the public as a way to convey the progressive ideals of Paul Robeson and the volunteers of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade.

By the mid-1930s, Paul Robeson had achieved international acclaim as an actor, singer, and public personality who criticized racism. The rise and expansion of fascism in Germany and Italy and other parts of the world intensified his concerns about the precarious state of democracy, freedom, and social justice. After the Spanish Civil War began in 1936, Robeson threw his support behind the elected government. “The artist must take sides,” he announced. He sang often to raise funds for children displaced by the war and appealed for assistance to the Spanish Republic.

In 1938, he and his wife, Eslanda, went to Spain to learn directly about the fascist threat and to support the soldiers defending democracy. Three years later, after Spain had fallen to the pro-fascist dictator, General Francisco Franco and World War II had begun, the American survivors of the Spanish Civil War made Paul Robeson an honorary member of the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade.

The ‘Robeson In Spain’ project also includes two lesson plans, multimedia primary resources, and an extensive bibliography to facilitate the teaching and learning about the Spanish Civil War and the commitment of men and women from other countries to preserve democratic ideals.

Who was Paul Robeson?

“The artist must elect to fight for freedom or for slavery. I have made my choice. I had no alternative.” – Paul Robeson, 1937.

The African-American Paul Robeson, a large man with a deep voice, achieved great distinction as an athlete, singer, actor, scholar, and supporter of social justice. Born in Princeton, New Jersey, Robeson graduated from Rutgers University with honors. He excelled in sports (All-American in football). He graduated from Columbia Law School in 1923 and married Eslanda Cordozo Goode. He won fame as an actor on stage and screen. In the popular musical Showboat, Robeson sang “Ol’ Man River.”

The African-American Paul Robeson, a large man with a deep voice, achieved great distinction as an athlete, singer, actor, scholar, and supporter of social justice. Born in Princeton, New Jersey, Robeson graduated from Rutgers University with honors. He excelled in sports (All-American in football). He graduated from Columbia Law School in 1923 and married Eslanda Cordozo Goode. He won fame as an actor on stage and screen. In the popular musical Showboat, Robeson sang “Ol’ Man River.”

The rise of fascism in Europe in the 1930s awakened Robeson’s political activism. He sang benefit concerts to assist Jewish refugees from Hitler’s Germany and to support Spain’s democracy during the Spanish Civil War. His mounting concern over fascist Germany’s and Italy’s direct support of the Spanish insurgents, and the western democracies’ refusal to assist the legitimate government, led him to visit the war-torn country in January 1938. He called his 1938 trip to Spain “a major turning point in my life.”He became an outspoken critic of U.S. segregation and lynching. In 1939, he recorded “Ballad for Americans,” a work that celebrated diversity and multiculturalism.

Robeson’s demand for equality and his opposition to the Cold War in the 1940s angered conservatives, who called Robeson a Communist. His refusal to be silent led to violent attacks at a concert in Peekskill, New York, in 1949. His criticism of the Korean War led the U.S. government to revoke his passport (later overturned by the Supreme Court), which limited his travels until 1956. He died after a long illness at the age of 77.

To learn more about Paul Robeson, see our bibliography.

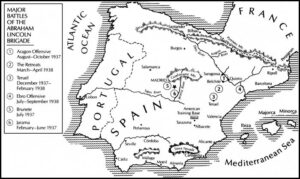

Civil War in Spain

The Spanish Civil War began as a rebellion, led by General Francisco Franco, against the legally elected Republican government in July 1936. The rebels opposed liberal changes, such as land reforms and provisions for women’s education, legal divorce, and the right to vote. In large cities, such as Madrid and Barcelona, civilian militias successfully resisted the military uprising, but Franco appealed to Europe’s fascist dictators, Hitler in Germany and Mussolini in Italy, who sent armed forces to Spain. In 1937 German planes bombed the town of Guernica, an atrocity that inspired Pablo Picasso’s most famous painting. The Spanish Civil War continued until April 1939, when the victorious generals captured Madrid.

Learn more about the Spanish Civil War here.

The Abraham Lincoln Brigade

European democratic countries feared that their intervention in the Spanish Civil War might provoke a second world war. To avoid that, the international community adopted a policy known as “non-intervention,” denying aid to both the legal Spanish government and the rebels. Starved for assistance, the Spanish Republic then appealed for voluntary help. This appeal was supported by the communist-led Soviet Union.

European democratic countries feared that their intervention in the Spanish Civil War might provoke a second world war. To avoid that, the international community adopted a policy known as “non-intervention,” denying aid to both the legal Spanish government and the rebels. Starved for assistance, the Spanish Republic then appealed for voluntary help. This appeal was supported by the communist-led Soviet Union.

Volunteers from more than 50 nations, numbering around 35,000 men and women, went to Spain, forming the International Brigades against fascism. To enter Spain, U.S. volunteers had to defy State Department orders that stamped all passports with the warning “NOT VALID FOR TRAVEL IN SPAIN” and pretend to be tourists. Nearly 3,000 volunteers from the United States served in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade or the American Medical Bureau to Save Spanish Democracy. About one-third of the Americans died in Spain.

Learn more about the men and women of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade here.

African Americans in the Spanish Civil War

About 90 African Americans volunteered in Spain, including Oliver Law, from Chicago, who eventually commanded the Abraham Lincoln battalion until he was killed in 1937. The only African-American woman was Salaria Kea, an Ohio nurse. The Abraham Lincoln Brigade was the first fully integrated army.

About 90 African Americans volunteered in Spain, including Oliver Law, from Chicago, who eventually commanded the Abraham Lincoln battalion until he was killed in 1937. The only African-American woman was Salaria Kea, an Ohio nurse. The Abraham Lincoln Brigade was the first fully integrated army.

Black volunteers were surprised and delighted to mix completely with whites without worrying about race prejudice or discrimination. “Spain was the first place I ever felt like a free man,” said soldier Tom Page. Later, during World War II, African Americans had to serve in U.S. units that were segregated by race.

View ALBA’s curriculum materials on African Americans in the Spanish Civil War here

Primary Resources

ALBA has selected a variety of rich primary documents, including multimedia resources, for use in the classroom.

Click here to view our Robeson Primary Resources.

From Alvah Bessie and Albert Prago, eds., Our Fight: Writings by Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade: Spain, 1936-1939 (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1987).

Lesson Plans

Lisa-Jane Shuman, a high school social studies teacher and alumna of ALBA’s Summer Teacher Institute, is the author of two lesson plans focusing on Paul Robeson and the fight in Spain.

The first lesson analyzes Paul Robeson’s decision to go to Spain during the Spanish Civil War and what his experiences reflect about African American Volunteers. The lesson makes use of the Robeson in Spain comic as well as multimedia resources from the web.

The second lesson aims to understand why the Spanish Civil War was viewed as an American problem by the people who went there. The guide makes use of the Robeson comic as well as ALBA’s Biographical Database of Volunteers.

Also available are topics for discussion, suitable for high school or college students.

Curriculum Materials

Web Resources

Paul Robeson Biography (Wikipedia)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Robeson

Paul Robeson and the Spanish Civil War (Wikipedia)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Robeson_and_The_Spanish_Civil_War

Paul Robeson Chronology (Bay Area Paul Robeson Centennial Committee)

http://bayarearobeson.org/Chronology.htm

Paul Robeson Timeline (PBS American Masters)

http://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/database/robeson_p_timeline_flash.html

Paul Robeson on the Web (Princeton Public Library)

http://www.princetonlibrary.org/robeson/links.html

Bibliography

Robeson in Spain is based on a number of textual and visual primary and secondary sources, including materials located in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives in the Tamiment Library at New York University. In addition to the books listed in this bibliography, our story relied on Eslanda Goode Robeson’s Spanish diary, excerpts of which were published as “Journey into Spain” in Alvah Bessie, ed., The Heart of Spain: Anthology of Fiction, Non-Fiction and Poetry (1952).

Any historical account involves narrative choices and requires interpretation, and graphic narratives have their own particular emphases and limitations; the choices made in this account are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Sheila Tully Boyle and Andrew Bunie, Paul Robeson: The Years of Promise and Achievement (2001).

Lloyd L. Brown, The Young Paul Robeson: On My Journey Now (1997).

Peter N. Carroll, The Odyssey of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade: Americans in the Spanish Civil War (1994).

Peter N. Carroll, Michael Nash, and Melvin Small, eds., The Good Fight Continues: World War II Letters From the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (2006).

Danny Duncan Collum, ed., African Americans in the Spanish Civil War: “This Ain’t Ethiopia, but It’ll Do” (1992).

Martin Duberman, Paul Robeson (1989).

Helen Graham, The Spanish Civil War: A Very Short Introduction (2005).

Paul Robeson, Here I Stand (1958).

Susan Robeson, The Whole World in His Hands: A Pictorial Biography of Paul Robeson (1981).

Sterling Stuckey, Going through the Storm: The Influence of African American Art in History (1993).

Credits

Illustrated by Joshua Brown

Written by Joshua Brown and Peter N. Carroll

Designed by Richard Bermack

Robeson in Spain is a special issue of The Volunteer, published by ALBA.

We are grateful for encouragement and financial support from The Puffin Foundation, Ltd., The Bay Area Paul Robeson Centennial Committee, Dr. Steve Jonas, Joan and Allan Fisch, David Cane, Michael Organek, John and Jane Brickman, and Paul Robeson, Jr.

We wish to thank our fellow members of the ALBA Board of Governors for their help, and to acknowledge the gracious assistance of Joellen El Bashir, Curator of Manuscripts at Howard University’s Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, where the Paul and Eslanda Robeson Collection is housed.

For information contact: [email protected].

Copyright

Copyright © 2023 Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives (ALBA).

The images may be copied by individuals or libraries for personal use, research, teaching or any “fair use” as defined by copyright law. Please include this statement with any copies you make. Non-commercial, non-subscription Internet editions created for an educational purpose may freely link to the site or individual pages.

Anyone interested in any other use of these images, including for-profit Internet editions, should obtain permission from ALBA, 212-674-5398 or [email protected].